The Copts and the Arab Spring

By H.D.S. GREENWAY

23/11/2011

When Egypt’s Anwar Sadat made his historic visit to Jerusalem 34 years ago, I was one of the reporters chosen to meet him along his personal via dolorosa in the Old City. My station was the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and I was told that I would be allowed only one question.

I waited in the gloom of that venerable space until, suddenly, Sadat stood before me.

“Mr. President, I know you are a pious Muslim,” I said. I could see the mark that comes to the faithful from touching foreheads to the floor in prayer. “What does it mean to you to be here in the very heart of Christianity?”

The president of Egypt looked me up and down and said, “Young man, I will have you know there are more Christians in my country than there are Jews in Israel.”

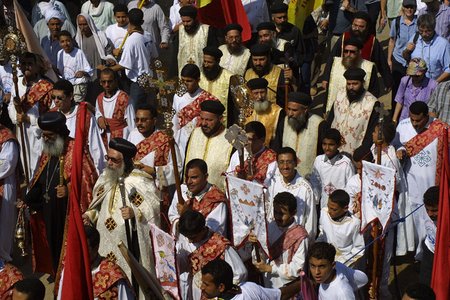

He was referring to the Copts, an ancient Christian community that according to tradition was introduced to Egypt by Saint Mark in 42 A.D. Copts comprise nearly 10 percent of Egypt’s 80 million people. Like the peace that Sadat wrought with Israel, the Coptic community is holding fast, but it’s feeling threatened by the Arab Spring.

Copts joined with Muslims in Tahrir Square to overthrow Hosni Mubarak, but the unity forged in that popular up-rising has not lasted.

Last month a peaceful march protesting the destruction of a church in upper Egypt was broken up by police and army troops in central Cairo. Twenty- seven people were killed, some of them run over by military vehicles, and more than 300 people were injured.

Reports from Egypt said state television had called on citizens to turn out and protect their army from cross-wielding Christians, and a melee ensued. The incident has become a cause célèbre in Egypt, and an internal army investigation, much criticized by human rights organizations, is proceeding.

Copts have long faced discrimination, but today, with the tide of political Islam on the rise, they fear that religious bias and violence against them may increase.

Western diplomats in Cairo told me on a recent visit that Copts were increasingly showing up at their embassies enquiring about emigration opportunities.

Wahib El-Miniawy, a former ambassador and a Copt, confirmed that many of his coreligionists felt under assault, though he insisted that he would never leave his country. It was not so much that Copts were not being allowed to build churches without hard-to-get government permission, he told me, but a deep-seated hostility towards Christians that began in elementary school.

That mind-set took hold soon after Gamal Abdel Nasser took power in Egypt in a coup in 1952. He appointed an ignorant minister of education, and the branding of Christians as “the other” began, El-Miniawy said.

In truth, Christians have been leaving the Middle East for decades. When Sadat came to Israel, Bethlehem was nearly 100 percent Christian. Today it’s 30 percent, many Christians having fled to North and South America.

The Iraq war saw a considerable exodus of Christians from Iraq. And whatever the other failings of Hafez and Bashar al-Assad in Syria, Christians in Syria were closely protected under their rule, perhaps because the Assads were from a minority — the Alawites — themselves.

Today, Syrian Christians are trying to stay out of the fray, but they, too, feel nervous about their future in the Arab Spring.

More broadly, since the breakup of the Ottoman Empire and the end of European colonial rule, many of the great polyglot cities of the Levant and North Africa have been shorn of their minorities. The establishment of Israel, and the Arab hostility to it, led many Jews to leave for the Jewish state. Baghdad, for example, had a large Jewish population that has now shrunk to a handful.

The vibrant Greek and Italian populations of Alexandria largely fled to their homelands following the virulent nationalism that Nasser introduced into Egypt. Muammar el-Qaddafi kicked thousands of Italians out of Libya. In Turkey, ancient Greek, Armenian and Jewish communities have all been sharply reduced.

There are many reasons for the exodus of these various minorities. But it would be a shame indeed if the Arab Spring and the fall of dictators led to a further unraveling of a vibrant cultural tapestry that once so enriched the lands bordering the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean.