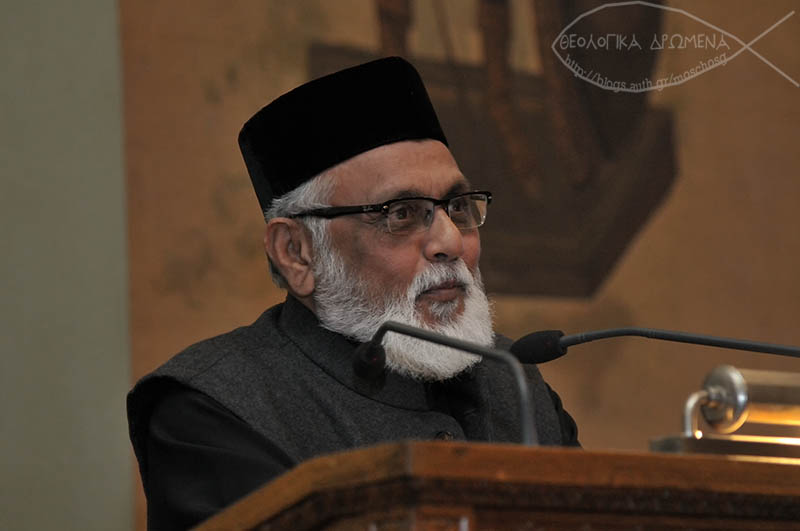

‘SYNODALITY, DEMOCRACY AND THE SOCIAL MEDIA’ – FR. DR. K. M. GEORGE (KONDOTHRA)

Pan Orthodox Cemes – 5/6/18

Your Eminences, Fathers, Professors, Sisters and Brothers,

I bring cordial greetings to you with full awareness of more than two millennia of intellectual spiritual and commercial exchanges between Greece and my country. As I put the words, “Synod” and “Democracy” in the title of my brief presentation, I know that these words and concepts originated in ancient Greek culture, both Christian and pre-Christian.

At the outset I wish to recall to memory the blessed visit in 2000 AD of H.A.H. Bartholomew, the Ecumenical Patriarch along with H E Damaskinos of blessed memory to our church in India, namely, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, that faithfully holds the tradition of St Thomas the apostle. Their visit was to promote the well-known dialogue between the Orthodox and the Oriental Orthodox families of churches. As you are aware the unofficial dialogue started in 1964 with the initiative of Prof. Nikos Nissiotis, then director of Bossey Ecumenical institute, Fr Paul Verghese (Later Metropolitan Paulos Mar Gregorios) from the Malankara Orthodox Church, then Associate General Secretary of the WCC and the Faith and Order Commission. This dialogue was taken at the official level in 1985 onwards, in meetings that took place in Chambesy, Geneva and Abba Bishoy Monastery of the Coptic Church in Egypt. Both the unofficial and official dialogues resolved the Christological dispute and came to the conclusion that both families of churches hold the same Apostolic faith, though linguistic, terminological and cultural issues in the 5th century exacerbated the Christological issue, and divided them. In a meeting in Chambesy, Geneva, follow up steps were suggested by the joint commission in order to bring the two families to full Eucharistic communion.

I have mentioned this in order to illustrate that the principle of Synodality (conciliarity) is central to Orthodox Ecclesiology. Although it may have phases of waxing and waning, it may reassert itself in spite of the time lapse of 1500 years, that is, between the council of Chalcedon in fifth century and the 20th century.

Let me say at the very beginning that I take the word synod in its etymological sense of “taking the way together” or travelling together (syn+hodos) because it provides a beautiful and tangible image to anyone in any cultural setting. I do not wish here to go into the technical meaning the word Synod has acquired in several churches, where it is a formal assembly of Bishops to transact official agenda. But In my ancient apostolic Malankara church in India today whenever we use the word synod for the meeting of bishops we qualify it with the adjective “episcopal”, because in our earlier tradition a synod meant a representative assembly of the whole church – laypersons and priests together with the bishops. This assembly is still the highest decision making body. Since lay representatives from parishes are proportional to the number of parish members, the majority in the assembly are lay people. They meet every five years, elect the regular governing bodies, and when necessary, elect the bishops and the Catholicos, and make necessary amendments in the constitution of the Malankara church. Every member weather lay, priest or bishop has only one vote.

The Oriental Orthodox Churches of Coptic, Syrian, Armenian, Ethiopian, Eritrean and Indian traditions conventionally acknowledge the three ecumenical councils of Nicaea, Constantinople and Ephesus. But in the light of the 20th century dialogue they would recognize Chalcedon and the rest on the basis of the Orthodox interpretation of those councils. The point is that though these oriental churches did not convene a common council after Ephesus they remained in the same apostolic faith in Christ and the Sacramental communion. So some theologians have raised a question whether an Ecumenical council is essential for the maintenance of the same faith and Eucharistic communion. But we know from our experience that in our contemporary world our faithful in both native countries and the diaspora face a great many questions of theological, ethical, pastoral, canonical and spiritual nature. Therefore, convening of a council like the Holy and Great council certainly is the need of the times.

Unlike in earlier ages when authority structures were very clear in church and society, our present world lives in conditions of confusion and uncertainty. On the one hand Emphasis on Individual freedom in a liberal democracy, and on the other hand great restrictions on individual freedom in theocratic societies and dictatorial regimes with fascist tendencies are both existing in our contemporary world. Secularism and irreligion coexist with religious fundamentalist and radicalist tendencies. In between such extremities the members of the church are seeking counsel and guidance.

We may identify at least a few Christological, Pneumatological and Trinitarian principles that underlie the practice of synodality in the Church.

1. The Pneumatological-Inspirational Dimension. The first Christian community arising from the Pentecost experience of the Holy Spirit in Jerusalem as described in the Acts of the Apostles relied on the power and guidance of the Holy Spirit. Their mode of life as a Spirit inspired Christian fellowship set the model for the later Church. Examples like the election of Matthias to replace Judas Iscariot (1:12-26), the election of «seven men of good reputation, full of the Spirit and wisdom» to minister as deacons (6:1-15) and the very first meeting of the synod of the Church. In the first Synod of Jerusalem, «the Apostles and elders, with the whole Church, decided.» (15:22) on crucial issues like circumcision, food taboos etc. The celebrated phrase «it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us» (15:28) became the fundamental principle of synodality in the Church. The experience of a genuine brotherliness and sisterliness in Christ and the consultative mode of church governance guided by the Holy Spirit constitute the synodal character of the Church. The way of life of the early church was synodical at its best. Whether it was a matter of election to a responsible position or urgent ethical-legal issues affecting the community there was a great effort to promote consensus among the members of the church and dependence on the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

2. The Christological-Anthropological Dimension. The New Testament vision of the fullness of the human person and of the human community is expressed in the image of Christ as the head and the Church as the body. The person of Christ, who dynamically unites the divine and the human, redeems humanity to his own fullness in the process of Theosis. The Church as the body of Christ stands for the human community and by extension all created reality that can experience God’s salvation in Christ. The person and the world at large as envisaged here are to be participants in God’s compassionate love and the saving process. Therefore, an appropriate Christological approach to anthropology and cosmology has to be evolved from the image of the Church as the Body of Christ. When the apostle Paul envisages that the individuals and the whole Church can grow to the full measure of the stature of Christ (Eph. 4:13) he means that humanity and all creation can aspire to grow into the infinite dimension of the Word incarnate. This is a never ending process of ascent, as in the ever continuing anabasis of Moses climbing the holy mountain of Sinai to experience the presence of God in thick darkness, a biblical image so dear to the Cappadocian fathers. We can also take other biblical images like the banquet of the kingdom, where people from East and West, from North and South take part, and we will get a glimpse of synodality in its broadest sense. Thus synodality is an expression of the ultimate Koinonia in and through Christ.

3. The Trinitarian-Holistic Dimension. The perichoretic unity in Trinity has always helped the Orthodox tradition to conceive its ecclesial structures. Here is a source of authority that negates all false hierarchies, and worldly human goals. Since there is no hierarchy in the Trinity in our worldly sense of order and number, as taught to us by the holy fathers like St Basil of Caesaria and St Gregory the Theologian, a genuine reflection of divine perichoresis in the Church would help us visualise the world in radically different ways. Our Lord Jesus very clearly draws a contrast between the mode of authority as exercised by rulers in this world and and the mode of authority exercised by the Christian Church. «You know that the rulers of the gentiles lord it over them, and those who are great exercise authority over them.» He is emphatic when he says to the disciples: «Yet it shall not be so among you; but whoever desires to become great among you, let him be your servant… Just as the Son of Man did not come to be served but to serve, and give his life a ransom for many» (Matt. 20:25-28). This is radically subversive in the sense that he turns upside down our sense of hierarchy and the order of our perceived reality. The values of the kingdom of God are clearly distinguished from the norms of the order of the world. Jesus literally exemplified this when he washed the feet of his own disciples.

Long before parliamentary democracy became an acceptable mode of governance in modern states, the Church led the way to practice its fundamental principles. Modern democracy, probably through biblical inspiration, took over some of these Christian elements. For example, in the British democratic system followed in the former British colonies, the bureaucrats are called civil servants or servants of the people. A minister in government is literally one who serves or a servant. Paradoxically the kind of privileges and positions enjoyed by these bureaucrats and ministers may not have anything to do with the life of a servant or the committed service of anyone who is inspired by the message of Christ.

Democracy loses its quality and power whenever the process of consultation and consensus is weakened. In big democracies like India elections are the decisive expression of the will of the people and the convergence of public opinion. In small communities there may be chances of direct debate and the effort to reach consensus. But elections, however well they are conducted, do not fully represent the public opinion in all its different shades. There is also the danger that they can be manipulated by big money and political power and intrigues. Parliamentary democracy, like in my country, projects a secular state in its constitution. Therefore, even if all the citizens of a country follow some religion or other, the secular state and its governance are supposed to take a distance from favoring any religion or promote the doctrines of one religion. In other words, a democratic system is not required to have any reference to a transcendent reality.

An Indian Buddhist Ruler. In the classical tradition of India one comes across a great ruler called Ashoka (ca. 268-239 BCE) who became the emperor of a large part of India some 500 years before Constantine became the Roman emperor. He accepted the Buddhist way of life and became a conscientious follower of the Buddha who had lived 300 years before him. Like Constantine who accepted the Christian faith and became its defender some 300 years after the Incarnate life of Jesus Christ, Ashoka became the defender of Buddhism, and sent out missionaries to Asian countries and to as far as the Mediterranean coast. He laid down all weapons after witnessing a bloody war with a neighbouring kingdom, became a great pacifist, embraced Ahimsa or nonviolence, and erected pillars and rock edicts throughout India urging the people to practise compassion to all creatures, care for the common good and toleration and harmony among various competing religions.

Asoka’s period illustrated «what the ruler and the ruled owed to one another,» as phrased in a recent article by Rajeev Bhargava, a political theorist in Delhi. (The Hindu, March 4, 2018). The Indian equivalent of emperor is Chakravarti. The Sanskrit word means “one who turns the wheel”. The chakra or wheel is that of Dharma ( Dhamma in Pali language), that is, law inspired by morality. Buddha turned the wheel of Dharma in religio- philosophical and the ethical spheres. You can still see in the state emblem of India a wheel adapted from an extant stone sculpture, with Ashoka’s edicts, erected in Sarnath in 250 BCE, (near the city of Benares), where Buddha preached his first sermon. Bhargava says that the turning of the wheel is a radical restructuring of the world in accordance with a politico-moral vision. The King initiates political and administrative measures inspired by public morality with the goal of justice, peace and prosperity to his subjects. Conquest of other kingdoms not by physical force but by the moral appeal of Dharma. The Pillar Edict 7 shows that compliance to dharma must arise largely from nijjihattiya (persuasion), not only from niyama (legislation). The people have to internalize dharma because it is good, not merely because the ruler so commands. Pillar Edict 6 speaks about the welfare and happiness of all living beings in this world and hereafter in heaven. The Buddha sent the missionaries on a totally peaceful mission. The principle was the welfare and happiness of all people (bahujanahitaya, bahujanasukhaya).

The king or ruler is not above dharma but is subject to the collective moral order that all people have to follow. The king is not just a ruler but the leader, a teacher, a father, a healer and a moral exemplar. These principles practiced by the Emperor Ashoka are relevant in modern democracy and its ideals of justice, tolerance, freedom, equality and civic friendship. «the Chakravarti tradition remains a valuable resource for our democratic republic» (Bhargava).

Social Media: the second decade of the 21st century is marked by the pervasive use and influence of social media -Facebook and Whatsapp, Twitter and Instagram…., in addition to the hundreds of TV channels and the traditional print media. Since we are in the thick of it as a totally new phenomenon we are unable to make a thorough judgement from within. In a political democratic system the role played by the social media is still being hotly debated.

There are positive and negative elements. Some of the positive features are:

*Unlike the print media and the TV channels, the social media provides an instant opportunity to debate or respond to an issue. *Participation of the people in a debate on common political and social interest can be maximised, provided all people can make use of the social media and there is complete connectivity. *All social hierarchies are abolished, and everyone irrespective of one’s position, age, religion, gender, nationality, location and profession can take part and voice one’s opinion in any issue. *A literally global discussion of any matter is possible since the net is literally worldwide. *The voters can directly interact with their elected representatives to bring their issues to the Parliament or Constitutional assembly. *The people can challenge their political leaders individually and collectively without fear of physical suppression or retaliation. *Mass movements for social and political change that once required a bloody political revolution can be organised on the Internet in a possibly nonviolent manner. These are some of the very important positive features that underscore the social media. In a way they are embedded as fundamental principles in the notion of democracy from the very beginning from ancient Greece to contemporary India.

The negative elements are now clear to all users of social media. *Generating and spreading fake news continues to haunt democratic governments in many countries. This is particularly venomous in times of election. *The enormous rubbish of words and images wantonly thrown on the net through social media does not build up society nor promote democracy in a creative way but undermines many of humanity’s venerable principles. *Human freedom in a democratic system that goes along with responsibility, care for the other and the concern for the common good is increasingly abused on the social media without any control. *Evil forces of jealousy and vengeance can jeopardise great educational and social causes. *The concept of Post-Truth itself arises mainly from the negative use of social Media in relativising factual truths and erasing all ethical norms in favour of political or financial gain.

In a post dated January 22, 2018 Samid Chakravarti, product manager of Facebook, discusses the effect of social media on democracy. (Hard Questions: What Effect Does Social Media Have on Democracy?). He frankly admits that the social media which was heralded as the technology of liberation at the time of Arab Spring can do damage even to a well functioning democracy. He laments that the Facebook, originally designed to connect friends and family, is being used in unforeseen ways with societal repercussions that were never anticipated, because unprecedented numbers of people channel their political energy through this medium. The use of social media as information weapon for cyber war, forum for hate speech, hoaxes, misinformation and disruption of social causes increasingly offsets its positive features. The phenomenon social scientists call «confirmation bias» is corrupting the value of social media since its users are drawn to information that strengthens their preferred narratives and reject information that undermines it.

Conclusion:

It is interesting that we are still confronting in a highly sophisticated technological way the old dichotomy of good and evil. In the cyber world any good that is created will instantly have its evil counterpart. Such is the ambiguity of human creativity that every good and useful software will have to face an equally or even more powerful and disruptive malware.

Now why did we speak about synodality in the Christian Church along with democracy in the secular world and the role of social media? The principles such as people’s participation, consultation and consensus that are conceived sacramentally and safeguarded liturgically and canonically in the body of Christ are used in the secular democracy without any transcendent reference. We used to say that the people, the body politic is the ultimate authority in a parliamentary democracy. Now with the emergence of the Internet and the social media this authentic principle is taken by many to crazy extremes where there is no reference to any authority or care for the common good. While the Church and the democratic state have built-in structures that can moderate the extremes of lawlessness or misuse of freedom, it is hardly possible in the present condition of social media. Well versed in classical Greek philosophy and literature St Gregory of Nazianzus in the fourth century called the body of that vast knowledge «bastard letters» because their logos did not connect to the Logos of God the Creator and Sustainer and the Redeemer of all that is. He wanted to take up the mission of leading those letters to their authentic source. We can probably use the same attribute used by that great and erudite Theologian to qualify the mind-boggling technological advances in the digital information universe. Now this places a very significant responsibility on the Church the Body of Christ which is the community of the Holy Spirit. The Church in faith and hope and love constantly calls upon the perfecting Spirit of God to provide authentic meaning and direction to the infinite potential of human creativity. The Church’s own in-house practice of the apostolic tradition of synodality and the style of life and governance that implies can set the standards for the secular world and all human aspirations.