Macedonia prey to global racket in holy icon theft

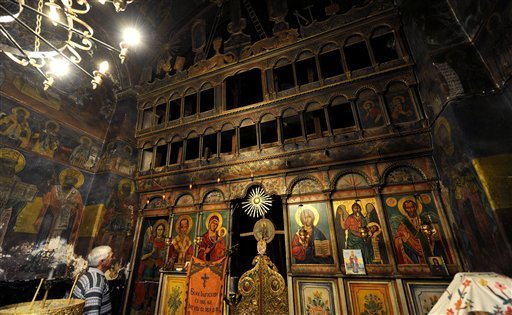

In this photo taken Thursday, Oct. 31, 2013, empty icon niches in the 19th-century church of St. George, where some 30 icons are missing, in the village of Lazaropole, near Debar, western Macedonia. Among the 30 icons stolen from the church in Lazaropole, high in the Macedonian massif, were 23 by the 19th-century Dico Zograf – one of the nation’s most famous painters. Zograf’s works can sell for tens of thousands of dollars on the black market.

Bishop Timotej- spokesperson of the Macedonian Orthodox Church

January 2014

LAZAROPOLE, Macedonia — The sumptuous altar screen in this village church rises in tiers of crimson, royal blue and gold leaf, all the way up to a crucifix flanked by dragons. Near the top, icon niches gape empty like blown-out windows.

The two dozen paintings were torn out in April, apparent victims to an art theft racket catering to rising international appetite for Orthodox religious paintings — a market worth tens of millions of dollars.

Arse Gligurovski, caretaker of the 19th-century church of St. George high in the Macedonian massif, says that every time he looks at the desecrated altar screen he feels as if “the robbers have ripped out and taken away our souls.”

Among the 30 icons stolen from the church in Lazaropole, high in the Macedonian massif, were 23 by the 19th-century Dico Zograf — one of the nation’s most famous painters. Zograf’s works can sell for tens of thousands of dollars on the black market.

Over the past decade, this small Balkan nation of 2.1 million has seen more than 10,000 religious artifacts stolen from its churches, including precious icons painted in the stylized Byzantine tradition. None of the works have been recovered. Thieves have removed whole sections of altar screens, altars, crosses, lamps and Bibles.

Macedonia’s art-rich rural religious sites, mostly dating from the 15th-19th centuries, are seen as the custodians of the predominantly Orthodox Christian country’s cultural and religious identity. The cultural heritage department says about 201 churches and monasteries are registered as national treasures. According to rough estimates, about two-thirds are poorly guarded.

“Most of the targeted churches are in remote villages, which are abandoned during the winter,” said Milco Georgievski, senior curator of the Icons Gallery in the southwestern town of Ohrid. “There are no alarms and anybody can open the doors with a simple kick. These are ideal conditions for robbers.”

Thieves mostly focus on churches in the western part of the country that borders Albania, and is dominated by ethnic Albanians — who make up about a third of Macedonia’s population.

One simple explanation is that Orthodox sites don’t resonate as much with the mostly Muslim Albanian minority. Authorities believe many of the thefts are masterminded in Albania, using an organized network of collaborators among minority regions.

“Albania is maybe only the collection center for stolen icons,” Georgievski said. “The speculation is that most are sold on clandestine auctions in western Europe and end up in private collections, including those of Russian tycoons.”

Saso Cvetkovski, director of the Doctor Nikola Nezlobinski Museum in Struga, says more than 500 “priceless” icons have been stolen from churches in the west over the past decade. The country has about 23,000 registered icons.

“It is difficult to estimate the value of this national treasure,” Cvetkovski said, “which has exceptional historical, cultural and religious value for Macedonia.”

In October, police in the Albanian capital of Tirana seized 1,077 stolen icons, frescoes and other pieces of religious and secular art dating from the 15th to the mid-20th century, including pieces from Macedonia.

Cvetkovski and another Macedonian expert visited Tirana in December to inspect the confiscated works and identified 21 stolen icons, whose return Macedonia is expected to formally request from Albania.

Georgievski said that he could not attach a value to the icons. But to give an idea of their worth, he explained that Macedonia’s five most valuable icons were insured for $50 million when they travelled to New York for an exhibition in 2004.

The task of guarding religious sites lies with the country’s Orthodox Church, and some say that is part of the problem: The church, which grew in influence after the collapse of communism in 1991, lacks specialized conservators who could care for the churches and their contents. And in many cases, local church authorities block moves to remove valuable works for safe storage elsewhere.

For example, the 19th-century church of St. Nicholas, in the village of Radozda, was targeted three times since 2012 before authorities agreed to remove some of the valuable surviving works. Caretaker Mile Skrceski says 23 icons from the altar screen were taken.

Bishop Timotej, spokesman for the Macedonian Orthodox Church said work is under way to document and register all icons in the west, and hopes that by the end of next year most will be housed in a museum planned to be built in Ohrid.

He added that “dozens” of the most valuable works have already been moved to a secret, safe location.

While it’s too late for Lazaropole, some 150 kilometers (90 miles) southwest of the capital Skopje, church caretaker Gligurovski still holds out hope that the altar screen can regain its plundered icons.

“They preserve the essence of who we actually are,” he said.