LIBERALISM AND FUNDAMENTALISM IN ISLAM AND CHRISTIANITY

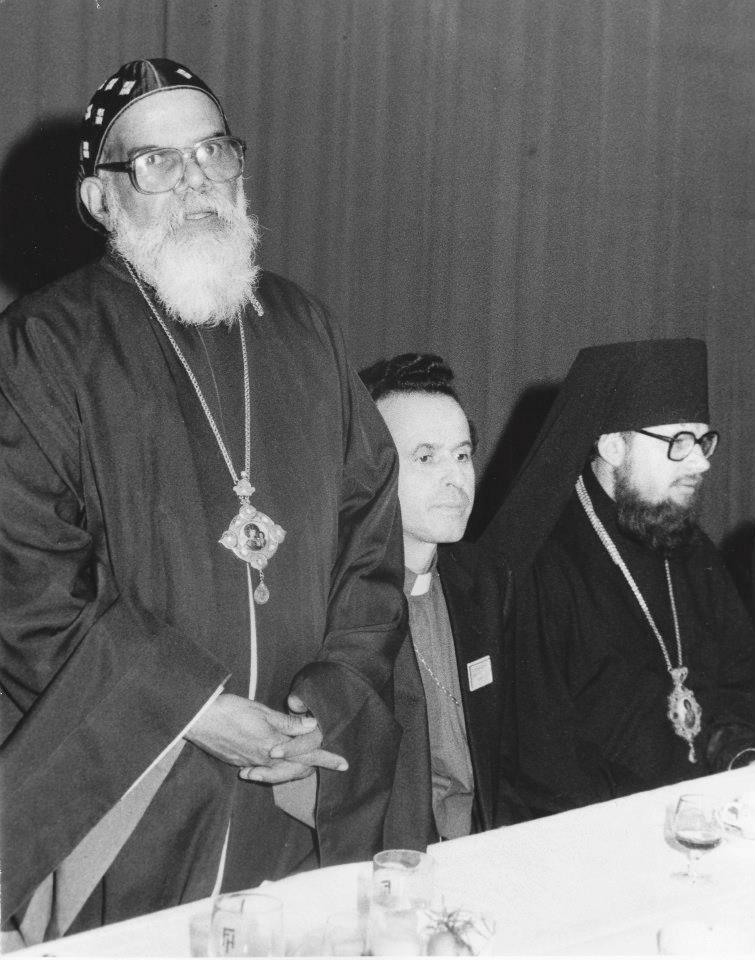

The Late Lamented Metropolitan Gregorious Paulose of the East

February 2016

Visit

http://paulosmargregorios.in/

A Comparative Study of How the Two Traditions Have Handled Modernism by the Late Lamented Metropolitan Dr. Paulos Mar Gregorios

The parallelism between the noticeably different ways in which two great world religious systems, namely Islam and Western Christianity, have handled the problems posed by the modern period and its secular civilization, are indeed striking. This paper seeks only to have a cursory look at these parallelisms and differences. A more adequate study, undertaken jointly by competent scholars on both sides, can be highly productive and useful for both religions in clarifying and correcting their own self-understanding as well as in improving their mutual relations.

Let me at this point state clearly that there is a great difference between the way Western Christianity (i.e. the Roman Catholic church and the Protestant Reformation churches) on the one hand, and the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches on the other, have handled this issue. Of the latter, i.e. the Orthodox, it can be said that as a church they have made no major effort to encounter the challenges posed by Modernity. They have by and large left the problem to be handled by the believers in their personal freedom. As far as the central issues of the faith are concerned, the Orthodox have chosen to live in conflict with modernity rather than come to terms with it in any particular intellectual approach.

One reason for this difference between the attitude and approach of the Western and the Eastern Churches may be that while Modernity was predominantly a Western phenomenon, and endemic to its culture, the Eastern Orthodox officially looked upon Modernity as a disease of the West and preferred to ignore it as a matter of no momentum to itself, or at best as something to be resisted, rather than reconciled with. Clearly the ostrich attitude of the East has been rather counterproductive in the outcome, resulting in the loss of millions of followers who preferred to adapt to modernity even at the risk of abandoning their faith. Those that have remained faithful have, however, done better than many in the West in holding on to the essentials of their faith. I am, however, by no means suggesting that the Eastern Orthodox attitude to modernity is the model to be emulated by all.

WHAT IS MODERNITY? WHERE IS THE CONFLICT?

Naturally, neither the word nor the concept “modern” is of classical or ancient provenance. Both the word and the concept were created in the modern period, i.e. post-Industrial Revolution. Its roots seem to be in the Latin word ‘modo’ which meant ‘current’ or ‘in fashion’. Of the writing of books on Modernity, there has been no end, as of now. Peter Berger, in his Facing up to Modernity (New York, 1977), suggested five phenomena as characteristic of Modernity: Abstraction, Futurity, Individualism, Liberation, and Secularisation. These may indeed be its marks, but its essence lies elsewhere. Max Weber was closer to the target when he identified the central feature of cultural modernity as THE SHIFT FROM RELIGION TO HUMAN RATIONALITY, AS THE UNIFYING FRAMEWORK FOR INTEGRATING OUR EXPERIENCE OF THE SUM TOTAL OF REALITY.

By human rationality, Weber means more than the instrumental reason which we use in our science and technology; he calls it “substantive reason”, more or less what others call “ontological reason” as distinguished from technological reason. This substantive reason was previously expressed in Religion and Metaphysics. In Modernity, this substantive reason is divorced from all Religion and Tradition, and domesticated within an autonomous human rationality, subsumed in three autonomous realms — Science, Morality and Art — free from all Religion or Revelation, Metaphysics or Tradition, totally freed from all dependence on any external authority outside of human reason. Weber’s intuition about the central feature of cultural modernity seems basically correct. In giving below my own basic intuition about the nature of cultural modernity, I acknowledge my indebtedness to Weber.

To be “modern” is fundamentally and primarily to affirm the freedom, autonomy, and sovereignty of the adult human person; hence, secondarily it is to repudiate totally all dependence on external authority — of God or Creator, Religion or Revelation, Scripture or Tradition, Metaphysics or Theology. The human person, in Modernity, acknowledges no authority above oneself, and one’s rationality is totally sovereign. Humanity owes its existence to no one else, and the autonomy of the human is not based on any Divine gift or mandate; it is by virtue of being human that the human person is self-sufficient, free and sovereign. There is no judge above human reason; if it is to be questioned or criticised, it can only be by that same reason — not by something higher than it or transcendent to it. The human reason alone lays down norms for itself — for action, for knowledge, for political economy; the free human persons legislate for themselves, and will not submit themselves to other people’s laws or religious laws.

Private property is an essential condition of this freedom of the Modem Person; for if one is economically dependent on others, one is not free, as Immanuel Kant, one of the Fathers of Modernity, pointed out.

My modern readers, with their highly developed critical rationality, should be able by now to recognize Modernity for what it is — the ideology of the newly emerging Burgher, the Bourgeoisie as their new ruling class of the Industrial Revolution, anxious to overthrow the authority of church and priest, of feudal baron and the traditional aristocracy; of the past as such with the dominance of Church and theology, of sacrament and priesthood, of the feudal Lord, and his traditional or past-derived authority. As one whose critical rationality is still rather underdeveloped despite years of western training, one never ceases to wonder about the historical fact that Marxism, which was supposed to be the ideology of the Working Class as opposed to the Bourgeoisie, remained basically within the structures of this Bourgeois Ideology of the Enlightenment and its Secularism. Dialectical Materialism is also a rationally derived ideology, a product of the same enthronement of the Human and its Rationality in place of God, sometimes calling this God either History or Nature. At this point, both Liberalism and Marxism, the two aspects of cultural-intellectual modernity, are equally unscientific; their foundations are in human desire and speculation, not in any kind of scientific objectivity. The basic assumptions of both Liberalism and Marxism can neither be scientifically proved or philosophically justified.

It is this modernity that came in head-on conflict with all forms of religion, especially the West-Asian traditions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, all of which affirmed the total authority of God, and regarded as the height of impiety to attribute to humanity such absolute sovereignty or unquestioned autonomy. That I believe is still the issue. The compromises which religion has made with Modernism in the last two hundred years will need substantive reconsideration in the light of what we today understand as the essence of modernity and our questions about its philosophical justification. Religions were too easily bedazzled by the dramatic achievements of science/technology, and wrongly took this as validation for the Secular Ideology, and the unproved and arbitrary assumptions behind that ideology which created modern Science and the Technology based on it.

Neither Modernity nor its enthronement of Critical Reason has any philosophical validity. These were unphilosophical affirmations of a ruling class which wanted to establish its authority over all. There is absolutely no philosophical or scientific justification for the claim that the human being is self-derived, autonomous and sovereign, recognizing no obligation to any higher authority. But this claim has been so often uncritically accepted even by religious thinkers and leaders. The end result has been that instead of directly exposing the fallacies in these ideologies, Religions have made compromises with them in a misguided attempt to salvage themselves.

It is in the light of the above understanding of the relation between Religions and Modernity that we seek to take a quick look at the historical developments in their relationships.

LIBERALISM AND MODERNISM

Both Liberalism and Modernism are primarily nineteenth century creations of the Christian Churches of Europe, later adopted by others. In the beginning, Liberalism had a pejorative sense, as reflected in the writings of Cardinal John Henry Newman, who called it tainted with the spirit of Anti-Christ. Writing in 1841, Newman spoke of ” the most serious thinkers among us” as regarding “the spirit of liberalism as characteristic of the destined Anti-Christ. Twenty-three years later, in 1864, Newman stigmatized Liberalism as “false liberty of thought, or the exercise of thought upon matters in which, from the constitution of the human mind, thought cannot be brought to any successful issue, and therefore is out of place”.

But Newman’s view was regarded as reactionary by many of his contemporaries; others like Edward Irving, (1826) saw the issue thus: “Religion is the very name of obligation… Liberalism is the very name of want of obligation.”

By the time we come to T S Eliot in the 20th Century, the more positive approach to Liberalism seems to take root everywhere, “liberalist” being opposed to “traditionalist, dogmatist, and obscurantist” – all three very pejorative terms now. Eliot wrote: “Liberalism is something which tends to release energy rather than accumulate it, to release rather than to fortify. It is a movement not so much defined by its end, as by its starting point; away from, rather than towards, something definite.” The characteristic feature of Liberalism now becomes unfettered freedom for enquiry and research, without fear or inhibition.

In the German Protestant Tradition, F C Baur (1792-1860) and Albrecht Ritschl (1822-1889) may be regarded as Fathers of what came to be called” Modern Critical Theology” based on an unquestioning acceptance of the claims of Modernity and on the unexamined acceptance of the canons of the now absolute authority of Liberalism’s critical rationality. For Ritschl, religious doctrines are merely human value judgments -Werturteile – on humanity’s attitude to the world. Roman Catholic Modernism was deeply affected by Baur and Ritschl; one reason why the Pope’s Syllabus of Errors roundly condemned Modernism and Liberalism. The Roman Catholic Church refused to bow before the Totalitarianism of the Enlightenment, which so to speak excommunicated all those who did not accept its canons as obscurantist and reactionary. One German thinker who saw through the pretensions of Modernism in the 19th century was Friedrich Nietszche (1860-1900). In his Untimely Observations – On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life (ET, Cambridge, 1980) Nietszche said an unqualified and angry “no” to Modernism’s attempt to unify all experience through the Dialectics of the Enlightenment — in particular to the historicist deformation of the modern consciousness, which is “full of junk details and empty of what matters”. Nietszche doubted whether Modernity could fashion its criteria out of itself, “for from ourselves we moderns have nothing at all” (op. cit., p. 24).

The second major internal critique of Modernity and the claims of the Enlightenment, always in Germany, came from the Frankfort School of Social Research. The Dialectics of the Enlightenment by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno (ET 1944) proclaimed loudly and clearly: “The Enlightenment is totalitarian” (p.6} and again: “The fully enlightened earth radiates disaster triumphant”.

Horkheimer and Adorno lampoons the European Enlightenment as setting out to master reality within its own categories: “From now on, matter would at last be mastered without any illusion of ruling or inherent powers, of hidden qualities. For the Enlightenment, whatever does not, conform to the rule of computation and utility is suspect”. They accuse Marx of having tried to reduce human reason to the mere Instrumental Reason of science and technology, ignoring the higher functions of Ontological or Substantial Reason which seeks emancipation and fulfilment.

The third and most recent European assault on Modernity has come from the PostModerns and Deconstructionists – Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Jean-Francois Lyotard, George Bataille, and all the rest. Their contention is that the project of modernity to capture and present truth through language, logic, discourse and critical rationality has totally and dismally failed.

But none of these critiques of Modernity touch its basic core – the affirmations about the total self-sufficiency, autonomy and sovereignty of the human person. Even post-modernity stays within that basic affirmation of Modernity – the patricidal denial of the Transcendent, and the consequent absolutization of the Secular, with its totalitarian taking over of all the universe and of all knowledge as subject to it. This is the point at which the battle should have been joined long ago between Religion and Modernity. And it is about time that that battle actually began.

ISLAM AND MODERNISM

I know so little of the cultural history of Islam that I have to ask my Muslim brothers and sisters ahead of time to correct me on any bloomers or blunders I am likely to make on the subject. Islam, battered and beleaguered by the technological superiority of the West and under the onslaught of its relentless imperialism, seemed to react to Western Modernity in spurts and spasms. The first wave already began in the sixteenth century, especially in the Indian sub-continent, where Islam had to contend both with other religions and with the strident culture of the Portugese. Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (1564 – 1625) and Shah Wali Allah (1703-1762) represent this first attempt of Islam to come to terms with the Industrial Culture and its incipient Modernity.

The second wave, beginning in the 19th century and spreading into the 20th, was more widespread, and embraced the Indian Sub-continent (Sayyid Ahmad Khan – 1817-1898; Ameer A1i 1849-1928, Sir Muhammad Iqbal 1877-1938); the Maghreb (Abd al-Hamid IbnBadis 1889-1940; Abd al-Kadir al-Maghrubi 1867-1907; Abu Shu-‘Ayb al-Dukhali 1878-1937); the Fertile Crescent (Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakabi 1854-1902; Mohammad Kurd ‘Ali 1876-1952; Shakib Ars1an 1869-1962, Muhammad Rashid-Rida 1865-1935) and Egypt (Muhammad Farid Wagdi 1875-1954, Ahmad Amin 1886-1954) and also Iran (Muhammad Hussayn Na’ini 1860-1936).

The Islamic Ummah was under brutal aggression not only from Enlightenment Rationality, but also from the aggressive military-technological imperialism, which was out to destroy Islam. Egypt, Syria and Persia, the heartland of Islam, had already been conquered and subdued. Along with successive military defeats, Islam suffered also from internal dissensions. The new plea was for Islamic Solidarity and resistance to the Aggressor. Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, the Persian (1839- 1897) urged mutual toleration among Muslims for the sake of the Umma. To this end he advocated the adoption of Western Science/Technology, at the same time preserving Islamic values. As a political agitator, he went to Afghanistan, Iran, Egypt, Paris, London and Istanbul, seeking to spread his views. Shaikh Muhammad Abdu of Egypt (I849-1905) was his disciple, a good bourgeois who underlined congruity between Islam and Modernity. Drawing again from the rich treasures of bourgeois individualism, he taught the principle of Ijtihad or the privilege of individual interpretation of the Scriptures. This gave one the freedom to violate some of the traditional interpretations of Islam without violating its fundamentals.