Iraqi Minorities Advocate for the Creation of New Provinces

If August 1914 shattered the received order of Europe forever, August 2014 dissolved the received tradition of protection for religious and ethnic minorities in Iraq and Syria. The lightening quick thrust of the Islamic State over northeastern Syria and down a broad band of Iraq in the summer of 2014 spelled disaster for the Assyrians, Chaldeans, Yezidis, Turkmen and other religious minorities that had been sheltered politically under the assumptions of so-called Sykes-Picot Agreement. Chief among those beliefs is that minorities had to be tolerated by any regime, whether colonial or indigenous.

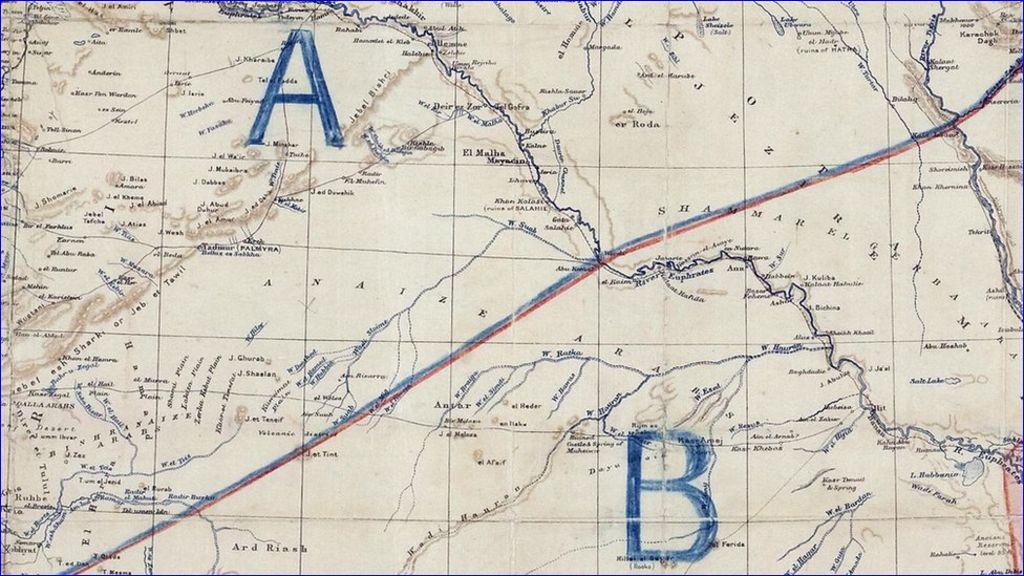

The Sikes-Picot Agreement — a secret partitioning of the Ottoman Empire negotiated by Mark Sykes of Great Britain and Francois Georges-Picot of France — defined future spheres of influence for their respective colonial empires.

ISIS rulers have often stated that one of their goals is to dissolve the borders created by this agreement and the assumptions of pluralism that were built into it. Since the Caliphate was declared two years ago, every minority in its path has faced brutality, torture, humiliation and slavery in the face of a helpless and hapless central government in Baghdad.

Just days away from the May 14 centennial of the ratification of the Sykes Picot Agreement that created the present borders of Iraq, the advocates for minorities are abuzz with plans to carve out new provinces that could be defended by ethnic militias.

On April 16, Andrew Doran, a Washington-based senior adviser to the In Defense of Christians nonprofit told a closed meeting of the Westminster Institute that he favored the creation of an autonomous zone for the Assyrians, Chaldeans, Yezidis and other minorities that have lived on the wheat-growing Nineveh Plain for centuries. The area of the autonomous zone under discussion ranges between 800 and 5,000 square miles.

“This is a time for radical creativity, a time to consider what a post-ISIL Iraq would look like,” Doran told the Westminster gathering. “Those who believe in sovereignty and self-determination for any minority group in Iraq have a right to demand the same sovereignty and security for Christians, Yezidis other minorities.”

In Baghdad, the members of parliament representing the minority constituencies that are spread like a patchwork quilt from Basra to Mosul are busy crafting proposals that could respond to the urgent needs of the minorities in a post-ISIS Iraq. A hot topic in Kurdistan is whether the Yezidi minority of 350,000 Kurdish-speaking citizens who live outside the border of the Kurdish Regional Government will vote in a referendum to form a semiautonomous zone in Sinjar defended by its own militia. The Turkmen of Iraq, who are concentrated in Tuz-Khurmatu, Kirkuk and Talafer, are advocating an autonomous zone for themselves.

“The Iraqi parliament must be serious to pass the law forming two new provinces, that is Tuz and Talafer, as well as the Turkmen Rights law,” said Dr. Ali Al Bayati, an official with the Turkmen Rescue Foundation in Baghdad and an advocate for Turkmen political rights. “Both of these measures already have been passed by the Iraqi ministerial council during the Al Maliki cabinet in 2013.”

Al Bayati added that coalition countries should provide funding for economic development to Turkmen regions, to spur the rebuilding of Turkmen cities destroyed by war and for military aid to recruit and train Turkmen defense forces and constabulary.

“The idea of an exclusive province for Christians is unacceptable to any Assyrian,” said David Lazar, an Assyrian immigrant to the United States who heads the Restore Nineveh Now Foundation. He added, “This is unconstitutional, according to the Iraqi constitution, and no Assyrian or Yezidi want such provinces. What we want are three new provinces in Nineveh Plain, Sinjar and Telafar to form a new region — a mini Iraq — tied to Baghdad as part of Iraqi Federalism.”

Doran agreed that a zone set aside for discreetly defined ethnicities is counter-productive. “There is a history of Christians, Yazidis and others’ living peaceably — though Christians and Yazidis have been victimized by Kurds and others,” he said. “The United States has to take into account where pluralism has worked, such as the Nineveh Plain, and where Christians and others have been victims. Peaceful pluralism is a wonderful ideal, but those groups who have been targets for discrimination and violence ought to be afforded a greater measure of autonomy. This doesn’t mean breaking up Iraq. It just means greater local governance.”

Doran said that he advocates for a safe zone that could welcome a range of minorities, including Christians, Yezidis, Turkmen Shia, Shabbaks and Mandeans.