Conference on Genocide and Reparations Under Way in Beirut

24/2/2012

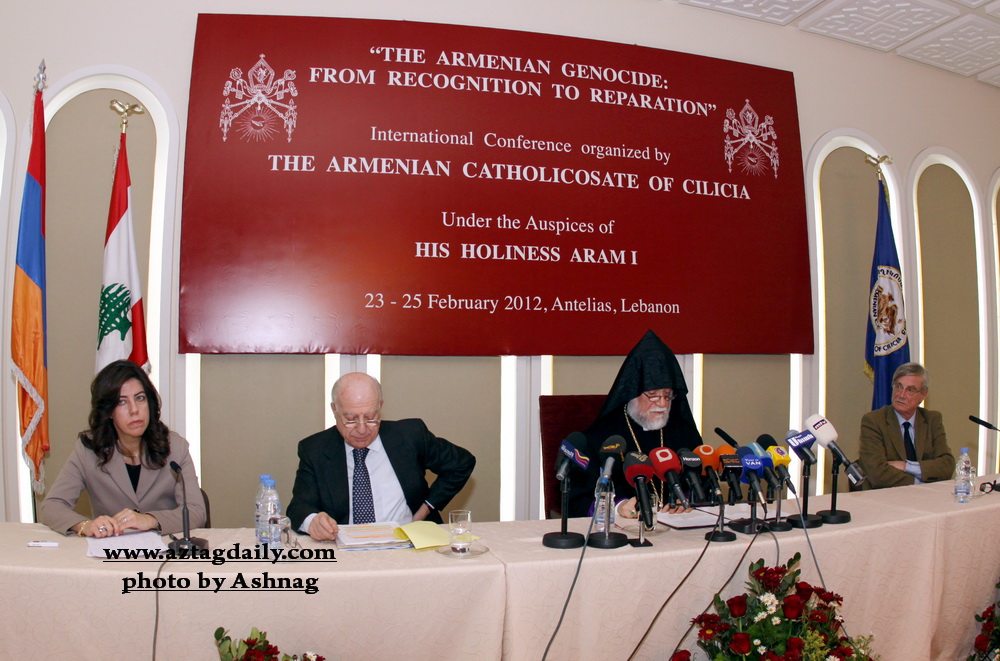

BEIRUT, Lebanon—On Feb. 23, the two-day international conference titled “The Armenian Genocide: from Recognition to Reparation” began in the presence experts from all over the world, ambassadors, current and former government ministers and members of the Lebanese Parliament, heads of Armenian religious communities and representatives of Armenian political parties and other institutions.

Catholicos Aram I welcomed the guests and the participants and explained the background leading to the conference. Discussing the issue of reparations, Aram I said, “Turkey must return the church and community properties confiscated by the Ottoman Turkish authorities to their legal owner, the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia. As the Catholicosate of Cilicia, we claim the ownership of our properties confiscated by the Turkish authorities.”

The Catholicosate of Cilicia held jurisdiction over more than 200 Armenian churches in the Ottoman Empire before World War I. Other Armenian churches, close to 2,000 according to church figures compiled by the Armenian Weekly, were under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate in Istanbul, the Catholicosate in Aghtamar, the Catholicosate in Etchmiadzin, and the Patriarchate in Jerusalem.

Prof. Nora Bayrakdarian introduced the agenda and the two speakers: H.E. Judge Fausto Pocar, Former President of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and H.E. Judge Joe Verhoeven, ad hoc Judge, International Court of Justice.

Judge Fausto Pocar said that although it is important to list the acts of the Genocide Convention, it is equally important to consider intent and incitement. After mentioning examples from the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and that of the Former Yugoslavia, he said that in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, the Tribunals clarified the crime of genocide by both applying the acts listed in the 1948 Genocide Convention and showing evidence of intent and incitement. Judge Pocar stated that the same process could take place in the case of the Armenian Genocide.

Judge Verhoeven began by saying that recognition of the Armenian Genocide is an established fact and that the Turkish State is denying part of its own history. He also said that the fact that the Genocide Convention had not been written at the time of the Armenian Genocide is irrelevant and that there is no statute of limitations on the act of the illegal killing of people. The State of Turkey and its territories still exist and it is therefore accountable. Speaking of Church properties, he said that these were semi-public properties: part of the historical heritage of the Armenian people and a necessary component of their identity. Turkey cannot deny the identity of a people. Turkey should respect it and make reparation to the Church, which is responsible owner of this heritage.

The opening session concluded with the anthem of the Catholicosate of Cilicia and the prayer of His Holiness Aram I at the Martyr’s Chapel.

Below are the introductory remarks offered by Aram I.

THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE: FROM RECOGNITION TO REPARATION

(Introductory Remarks by Catholicos Aram I)

I warmly welcome you to this spiritual center of the Armenian Church which is indeed a place of living encounter and interaction between peoples and perspectives. I extend my deep thanks and great appreciation to all of you and particularly to the experts of international law and Armenian Genocide for accepting our invitation to join us in addressing critical issues and questions pertaining to the Armenian Genocide.

The decision of US House of Representatives to urge Turkey to return confiscated churches and church properties to their rightful owners, and the approval of a bill by the French Parliament and the Senate making it a crime to deny the Armenian Genocide, along with the Turkish government’s aggressive reaction, have, once again, brought the Armenian Genocide to the fore of international headlines. The Armenian Genocide is no longer an exclusive concern of Armenian-Turkish relations; it has become integral part of the global agenda.

The conference will focus on how we can move from recognition of the Armenian Genocide to reparation. What procedures and mechanisms are provided by international law to effect this transition? What are the prospects and challenges before us?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948, had an immense impact on the self-understanding of human beings and the self-affirmation of nations and societies. Seeking to protect human dignity, promote justice, build greater peace and generate reconciliation, it also challenged the dictatorial governances and discriminatory patterns and norms existing in many cultures and societies.

The core values and basic principles contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, namely the fundamental right of human beings for life, freedom and dignity,[1] are also taught by Christianity. The Bible is the source of human rights.[2] According to Christianity, human rights are God-given, not man-made. As such, they should be recognized, respected, protected and promoted by all human beings, nations and states under any circumstances. To violate human rights is to reject God’s gift of life, freedom and justice; hence, it is a sin against God.

Human rights are not optional; they are integral to the Gospel message. Human rights advocacy is an essential dimension of the prophetic vocation of the church. To deny this commitment, is to negate the very being and the missionary calling of the church. Human rights in general and the Armenian Genocide in particular, are part of the missionary calling of the Armenian Church and they occupy, therefore, an important place on the agenda of its witness.

Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has been bolstered with broader networks and mechanism of implementation through treaties, resolutions and conventions, human rights violations have continued, and the UN and the international community have failed “to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance”.[3]

Therefore, the implementation process and enforcement system of human rights need to be strengthened, and early warning systems need to be activated. Furthermore, the efforts of non-governmental organizations, academic institutions and other actors in civil society, should be supported by all those who wish to transform societies and build a better world.

The resolutions of the Commission on Human Rights, including the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Violation of International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law and, generally speaking, the international criminal law provide an important legal context and juridical framework for matters concerning genocide and war.

In fact, acts committed by Turkey in 1915 are defined in the Convention as Genocide. The Turkish government intended “to destroy, whole or in part, a national, ethnical, social or religious group, as such”;[4] they “killed members of the group”; they “caused serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group”; they “deliberately inflicted on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part” ……..”;[5]

These acts constitute genocide as defined in the Convention and are punishable, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law”.[6] The Convention states that all those persons who have committed genocide “shall be punished”[7], whether they are “constitutionally responsible rulers, public officials or private individuals”.[8] And those persons who are charged with genocide shall be tried either in the territory where the act was committed or by an international penal tribunal[9]

The term “genocide” only became part of the vocabulary of international law in 1944[10]; however, the carefully planned and systematically executed attempt of the Ottoman-Turkish government in 1915, which aimed at the total extermination of the Armenian Nation, fits the definition in the Genocide Convention. This act, strongly substantiated by the historical evidence and eye-witness accounts of Armenian and non-Armenian, including Turkish sources, was unequivocally a genocide. The Turkish authorities may deny that it was a crime against humanity; some nations or governments may still keep silent about it for geopolitical reasons. But denial is a dead end. Negationism will eventually fall short before the truth. The retroactive application of the Convention is a critical issue which will be certainly treated by the Conference. Since only a state that has accepted the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice may submit a case to it, I hope that the Republic of Armenia will soon study this matter and take the necessary action. Are there some other possibilities for legal action, such as taking the Armenian Genocide to a national tribunal or creating a special tribunal or taking it to the European Human Rights Court? These questions need to be addressed from a juridical perspective.

In stressing the crucial importance of the promotion, protection and restoration of justice, the Commission on Human Rights affirmes the right of crime victims “to access to justice,” and spelles out various aspects and procedures of “remedy and reparation” for the “victims of violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. [11]

Regarding the process of reparation, the following issues require scrutiny:

a) The Commission provides a broad definition of victim, stating that “a victim” may also be a dependent or a member of the immediate family or household of the direct victim” .[12]

b) The victim’s effective access to justice includes “all available judicial, administrative, or other public processes under existing domestic laws as well as under international law”.[13] Within the context of the restoration of justice “adequate provisions should also be made to allow groups of victims to present collective claims for reparation and to receive reparation collectively”.[14] And, “reparation should be proportional to the gravity of the violations and the harm suffered”.[15]

c) The state or government under whose authority the genocide occurred is obliged to provide reparation. However, if the state or government responsible for the genocide is no longer in existence, “the State or Government’s successor in title should provide reparation to the victims”.[16]

d) The Commission on Human Rights refers to three forms of reparation: restitution[17], compensation[18] and rehabilitation[19]. These concepts or forms of reparation may have different connotations and implications in different socio-political contexts and in relation to specific cases. How do they apply to the Armenian Genocide?

For decades we have focused on the recognition of the Armenian Genocide by Turkey and the international community. In fact, the recent Court cases against American, Turkish and French insurance and private companies; the decision of US Congress to urge Turkey to return churches and church-related properties to their owners, and the Turkish government’s decision on 27 August 2011decided to return to the minorities the properties confiscated since 1936, came to re-emphasize the crucial importance of reparation. Indeed, recognition of truth implies reparation; these acts are intimately interconnected. This is at the heart of international law.

On the 100th Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, should we accept a symbolic formal apology and recognition by Turkey of the genocide? Should we claim financial compensation for the victims of Genocide and for the properties? Or, should we claim the return of church, community and personal properties? Further, should we demand that reparation include the damages that the Armenian people were subjected to during the “white genocide”, namely the constant threat to the Armenian identity in a diaspora situation that was caused by the “red genocide”? Should we, finally, consider land reparation within the provisions of international law?. The formal recognition of the Armenian Genocide is a conditio sine qua non for any attempt or process aimed at restoration of justice. And, as a first concrete step in the direction of reparation, Turkey must return the church and community properties confiscated by the Ottoman Turkish authorities to its legal owner, the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia. As Catholicosate of Cilicia, which was established in the 10th Century in Cilicia, south-western part of present Turkey, and which was in 1915 forcefully uprooted from its historical seat, we claim the ownership of our properties confiscated by the Turkish authorities.

It is with this objective in mind that we have set the agenda of this conference.

[1] Cf. Human Rights, Articles 1, 3.

[2] Cf. Isa. 61:1, Mt. 25: 35-40, Gal. 3: 28.

[3] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Preamble.

[4] Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 2.

[5] Convention, Article 2.

[6] Convention, Article 1.

[7] Ibid., Article 4.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., Article 6.

[10] Raphael Lemkin coined the term “genocide” in 1944 and that paved the way for UN to adopt the Conventio on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

[11] Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Violation of International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (Annex to Commission on Human Rights), II, c, d, e.

[12] “A person is a victim where, as a result of acts or omissions that constitute a violation of international human rights or humanitarian law norms, that person, individually or collectively, suffered harm, including physical or mental injury, emotional suffering, economic loss, or impairment of that person’s fundamental legal rights”. Ibid., V.

[13] Remedy and Reparation, VIII, 12.

[14] Ibid., VIII, 13.

[15] Ibid., IX, 15.

[16] Ibid., IX.

[17] “Restitution should, whenever possible, restore the victim to the original situation before the violations of international human rights or humanitarian law occurred. Restitution includes: restoration of liberty, legal rights, social status, family life and citizenship; return to one’s place of residence; and restoration of employment and return of property” .

[18] “Compensation should be provided for any economically assessable damage resulting from violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, such as: a) Physical or mental harm, including pain, suffering and emotional distress; b) Lost opportunities, including education; c)Material damages and loss of earnings, including loss of earning potential; d)Harm to reputation or dignity; and e) Costs required for legal or expert assistance, medicines and medical services, and psychological and social services”

[19] “Rehabilitation should include medical and psychological care as well as legal and social services”.

787025 931261I genuinely treasure your work , Wonderful post. 402240