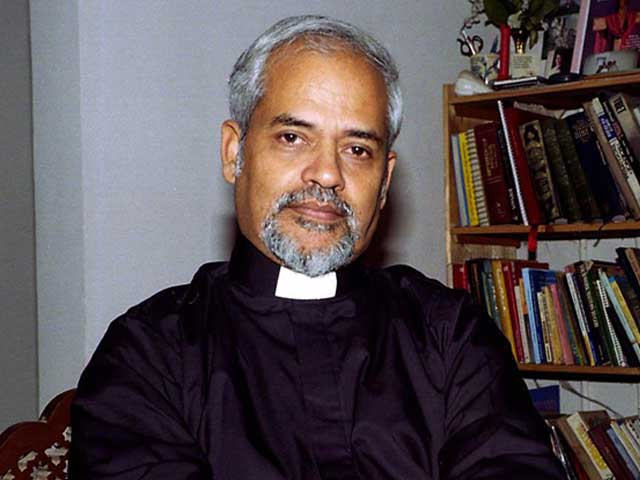

COMMEMORATING METROPOLITAN GEEVARGHESE MAR OSTHATHEOS – REV DR VALSON THAMPU

Rev Dr Valson Thampu

The Late Lamented Metropolitan Mar Osthathios Geevarghese of India

Rev Dr Valson Thampu- (Editor – Ecumenical Spirituality) OCP News Service – 2/12/18

Sermon preached at his memorial meeting at St. Paul’s, Mavelikara, on the 11th of February 2018.

Text. “Repent, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand!” -The Gospel According to St. Matthew 3:2.

More on Metropolitan Ostathios Geevarghese here:

PART -I

It is a century since the departure of Metropolitan Greevarghese Mar Osthatheos. I am not a member of the Malankara Orthodox church, but I resonate, by convic-tion and kinship, with the orthodox spiritual tradition. I have not met this saintly prophet-priest in person, whose memory continues to inspire tens and thousands of sons and daughters of the Malankara Church far and wide. But I have never been alien to the essence of the Orthodox tradition in its core significance; espe-cially thanks to the fatherly love and inspiring guidance received, for years, from Metropolitan Paulos Mar Gregorios during the time we shared in Delhi.

A few words now on why I feel a strong feeling of spiritual kinship with Mar Os-thatheos Thirumeni. In acknowledging this, I must admit that my acquaintance with his person and his many-sided ministry is second-hand. What do I find in this admirable disciple of Christ?

First, Osthatheos Thirumeni was a passionate preacher of the Word. Those who write on his pre-eminence and uniqueness among preachers, lay emphasis on his thundering voice, his fiery, prophetic spirit and his fearless application of biblical ideals and norms to contemporary social situations. Thirumeni did all of that; and with unforgettable vitality too. But that is not, to me, the heart of the matter. It is, I beg to submit, that Thirumeni was committed to incarnating the Word, rather than preaching on biblical texts. I need to make this aspect of his radical work clearer, if I can.

St. John, the Evangelist, leads us to the threshold of the mystery of the Word as, perhaps, none else has done, in saying, “The Word became flesh and dwelt in our midst, full of grace and truth. (Jn. 1: 14). To me, the core spiritual insight, if at all we abide by the genius of Incarnational Spirituality, is that scriptural texts become the Word only when they are ‘translated’ into lived realities. It is my ardent faith that, for Osthatheos Thirumeni, Jesus was the Word. All of the Bible is the way that leads up to him. That is why St. Paul testifies that in Jesus the fullness of Godhead dwelt richly. The words of the scripture are a medium -the spiritual al-phabet- for the revelation of the Word. The prime task of the preacher is to par-ticipate, together with the audience, in this mysterious process of the Bible be-coming the Word so that in the life of the believer and of the faith community the Word can become flesh.

It was for this reason that Osthatheos Thirumeni laid strong emphasis on the per-son of the preacher. Rather than hold forth in terms of prescriptions of norms, or denunciations of deviations, in this regard, he lived what a preacher should be – a life in consonance with the spirit of the Word. In preaching, he sought to become the Word. He brought his audiences into an awareness of this ultimate reality. It was this that moved the hearts of his enthralled listeners.

Thirumeni knew that two things were of utmost importance in this process. First, the preacher should lead an exemplary and impeccable life. The messenger should live the message. One aspect, among many others, of this discipline is that he purified the proclamation of the Good News of all selfish interests. He renounced every consideration of personal gains -whether it be in the form of money, or of popularity, or of reverence- from witnessing the Word.

Secondly, he believed that the Bible as a whole is an organic entity in revealing the Word. No one unfamiliar with the Bible in its entirety, he insisted, should dare to preach even on a single text. This insistence, I believe, is very salutary; for this is a necessary guarantee against misinterpretations, willful or otherwise. Even the devil quotes scriptures; but the devil quotes the Word selectively, because he is a calumniator of the Word. He seeks to subvert the Word through a slanted dep-loyment -as in the garden of Eden- of scriptures in parcels of convenience. Cherry-picking texts of comfort or convenience amounts to be a rebellion against the au-thority of the Word. We take the Word on our terms, rather than put ourselves under its authority.

Regrettably, this pernicious practice is ubiquitous in Christendom and is rampant in convention circuits. It is presumed that certain texts in the Bible alone are con-vention-friendly; as though the rest of the Bible is a sort of sanctified irrelevance! Of course, a preacher must concentrate, for practical reasons, on particular texts. But, in doing so, he must carry with him the full counsel of the Word. Unless the part -the chosen text- is interpreted in faithfulness to the Whole -the Bible- there is every likelihood of the chosen text being distorted towards legitimizing wrong motives and agendas.

This involves a hidden insult to the Bible. And it has been in practice for a long time. Preaching the Word is a solemn and sacred responsibility. That is why James warns, “Not many of you should become teachers” (James 3:1). Who doesn’t know that the undisciplined and indiscriminate preaching of the Bible -misunderstanding texts, and misleading the people into believing that what is be-ing belaboured is indeed the Word of God- has been, right through the history of our faith, the principal cause for dissension and disunity. The Word has been used to fragment Christendom; whereas it was meant to secure the unity of human-kind.

In point of fact, Osthatheos Thirumeni was not a preacher cast in conventional moulds. No one who ever heard him missed the prophetic power of his proclama-tion. That was not a matter of lung power! When God revealed himself to Elijah as the still, small voice (1 Kings 9:11-13), a great and eternally relevant principle was revealed. The power of the Word is independent of the power of man. It stands under the authority of God. God is love. Love, when expressed and experienced, becomes truth. Where there is love, there will always be truth. And where there is no truth, there is no love either. The voice of love and truth is always the ‘still and small’. The preacher, even when he proclaims at his loudest needs, himself, to hear the ‘still, small voice’ of God as love and truth.

Compared to the awesome power of God -that shakes the wilderness (Psalm 29:8)- man’s voice, no matter how magnified, will always be feeble in its physical aspect. So, the power of proclamation is not to be equated with the lung power of preachers. But there is power; awesome power. That power is the power of truth, refined and exalted by earnest discipleship. A preacher is a noise-polluter, if he does not speak the truth in love. That is the hallmark of the prophet: he speaks the truth in love. Hence the prophetic speech formula, “Thus says the Lord…”. The prophet, as Spinoza pointed out, is only a ‘translator’. He renders the will of God intelligible to a people. God is love.

Osthatheos Thirumeni was a prophet because he loved; not because he had some exceptional mastery over the language or extraordinary rhetorical fire-power in speech. When prophetic discipline of this biblical kind is excluded from sermons -misleadingly and indiscriminately labelled as “ministering the Word of God”- ser-mons become no more than performances. It becomes an art. The function of every art form is to entertain. The problem is that ‘entertainment’ is an alternative to edification and transformation.

It is not an accident that the very first biblical text on which Osthatheos Thirumeni preached was the 2nd verse of the third chapter of the Gospel According to St. Matthew, the reason I have chosen this passage as the text for this memorial message.

But there is a concern that I need to flag here. It is all very tempting to exalt Os-thatheos Thirumeni as a prophetic preacher of yester years and to remain satis-fied with renewing that noble and necessary memory. I am pretty sure that he would be unhappy, if we stopped with that. Why do I insist on this? Well, it is be-cause I know what a fiercely loyal and deeply devoted servant of the Malankara Orthodox Church Thirumeni was. A church is not an organization that runs routine programmes, including conventions and crusades. The church of Jesus Christ -which is what the Orthodox tradition is- must be a nursery, a place of growth, for the children of God. Its prime calling is to equip the saints. Some of them become preachers. But all are to be saints, if St. Paul is to be believed. Saints are quintessential prophets. They may not be fiery, thundering preachers. They are, in themselves, authentic, life-changing sermons. They are the still, small voice that shakes the wilderness of human existence, where people live alienated from God.

In the final analysis, exemplary children of God like Parumala Thirumeni, Ostha-theos Thirumeni, Pathros Mar Osthatheos, Thoma Mar Deevanyasos of Tabor Dayara, Paulos Mar Gregorios and others, are the fruits of a tradition -the Malan-kara Orthodox spiritual tradition- and not giants impressive and commanding in themselves. They were nurtured by a tradition which they, in turn, re-vitalized. Jesus is the soul of that tradition. The function of a tradition is to nurture men and women of faith. The proof of its vitality is not its material elaboration or organiza-tional proliferation; but the quality of the people it nurtures. It is unspiritual to see preachers and church leaders in isolation from the flock. That was precisely the fatal mistake that the Judaic establishment committed. This corrupted the Jewish religious establishment, and made it progressively irrelevant to the life of the people. As a result, when Jesus regarded the condition of the people at his time, they were like “sheep without a shepherd” (Mtt. 9:36).

This leads us, naturally and inevitably, to the second thing that I admire most in Osthatheos Thirumeni -his idea of priesthood. To him a priest, if he is indeed a servant of God, must have three dimensions. To put this in his own picturesque words, “When he stands, facing East, leading worship, he is a priest. When he stands, facing West, he is a prophet. When he is among the people, he is a shepherd.” I would venture to suggest that this insight -which articulates the core of the Orthodox spiritual tradition- is the most contemporaneously relevant em-phasis that Thirumeni has made. Barring rare and glorious exceptions, today priesthood in all segments, or limbs, of the Church, are in a state of spiritual anaemia. The paradox is that it is not in the interest of any church that its priests become narrowly -and, shall I say, comfortably? – confined to the physical boun-daries of the church and, even more regrettably, to routine exercises in pastoralia -important and necessary though they are. Osthatheos Thirumeni was ardently faithful to the church. But, to him this faithfulness mandated a continual outwork-ing of his discipleship to Jesus in relation to the larger social context. Jesus was his role-model. Jesus was Shepherd-Prophet-King in a seamless fashion. There was a prophetic touch to his pastoral ministry and a regal note of authority in his teach-ing ministry. No one will dispute that it was this fullness that Osthatheos Thiru-meni sought so very zealously to incarnate. That is why he has left a memory that we shall not willingly let die.

Passion for social justice, in all its cutting edges, was the prophetic fire in Ostha-theos Thirumeni, as it indeed was in Parumala Thirumeni. Social justice needs to be embraced by the church as basic to the faith community being the salt of the earth and the light of the world (Mtt. 5:13-16). The Kingdom of God is the incar-nation of God’s justice in the order of creation as a whole. The mustard seed of social justice sprouts in Jesus’ unforgettable saying, “the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (Lk. 9:58). As long as greed and affluence rule the world, social justice will be a forbidden agenda.

Wealth, in Thirumeni’s view, was the insuperable wall separating neighbour from neighbour. It is a sin, he thundered, to be rich in a starving society. Predictably, he was suspected of being a crypto Communist! It was reminiscent of the plight of Helder Camara, the South American Catholic bishop who said, “When I distributed charity to the poor, they called me a saint; when I asked why they were poor, they called me a Communist.” It is a historical fact that there would have been no Karl Marx without Jesus of Nazareth. Osthatheos Thirumeni was never apologetic of his advocacy for the poor. Like Mother Teresa, he identified himself with them. His life was a sermon of “Good News to the poor” (Lk. 4:18). It remains a robust and revolutionary challenge not just to the Orthodox Church, but also to Christendom at large.

Justice is the core prophetic agenda. It is when we thirst and hunger for justice -which is the same as praying, “Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven”- that we move into the zone of prophecy. It is a matter of great encouragement for all Christians as well as those who have any sense of godliness at all in any sphere that such a voice was heard in the wilderness of Kerala and diverse parts of the world through Osthatheos Thirumeni. Though unworthy to be bracketed with him, I am proud to belong to this tradition; especially at a time when different churches seem to succumb to the allurement of affluence, surrounded by the stink of corruption it generates.

I often wonder how Osthatheos Thirumeni interpreted the story of Lazarus and the rich man (Lk. 16). Such an instance, real or improvised, could have occurred only to a prophetic imagination. I am quite certain Thirumeni would have empha-sised, in his characteristic fashion, the economic and political link between the rich man and the body heaving with pain at the gate. The perennial truth is that the Lazaruses of this world are the creation of a handful of rich men. Poverty is not an accident; nor is it anyone’s fate. For a long time, I thought the rich man in this story could not reach out to the poor, dying Lazarus at his gate because he was immobilized by his indolent, soulless way of life which was too small and narrow to accommodate anyone but himself, which is often the case. But that is not how I see this text now. I am pretty sure that the rich man was afraid of approaching Lazarus. That he was stung by guilt. He knew that the wounds festering on La-zarus’ emaciated body were inflicted by the knives of his greed. Lazarus at his gate was a spiritual charge-sheet already pending in the Court of God against his murderous covetousness. The rich man was simply afraid. He was on trial. At La-zarus’ death, the verdict was pronounced on him, “Guilty!”

That is where social justice should come in. Social justice should not be mistaken as charity to the wretched of the earth. It is, in truth, a necessary investment in social sanity. That is why it figures very prominently in the Preamble to the King-dom of God. Osthatheos Thirumeni was concerned that the growing gulf between the rich and the poor wound degrade the garden of life into a wilderness of vi-olence and anarchy. This aspect of his spiritual vision will only grow in its radical relevance in the years ahead.

A third aspect of Thirumeni’s spiritual witness found expression in serving as a role-model to many who looked up to him in affection and respect. This was the hidden aspect of his long and fruitful ministry. He was a servant of God ‘sent’ into the lives of many, to build them up on the enduring foundation of godliness. If the case studies of those who have been so influenced and inspired were to be ga-thered together, it would burgeon into a veritable library.

But, being a role-model in the Orthodox spiritual tradition means living and serv-ing as a burning finger pointing many to the Lord. Osthatheos Thirumeni was nev-er in any doubt that Jesus was the Ultimate Role-model. A believer becomes a role-model only to the extent that his life reflects the light of life that Jesus is. It is because Jesus is the light of the world (Jn. 9:5) that we can be lights of the world (Mtt. 5:14).

I cannot help making a brief mention of a radical -and seemingly unorthodox- as-pect of Thirumeni’s life and witness. His spiritual vision had a borderless breadth. He could embrace and enfold anyone in it, even the irreligious. It is not often that we hear a Christian leader saying, even today, that Marx and Castro too should have a place within a contemporaneously radical vision of spirituality, provided the atheistic deflections of their thinking and advocacies are excluded. Thirumeni knew that the justice agenda would be still-born, but for God. God is the well-spring of justice. The church cannot witness Christ Crucified without serving as a voice in the wilderness, crying for social justice. That ‘voice’ needs to be an incar-national force. The church must practise what it preaches. This transforms the Church into an oasis of righteousness in the wilderness of life.

In what I have noted above, I have been necessarily brief and selective. The intent was only to acknowledge the spiritual bridge that links me to the authentic Or-thodox tradition that I found exemplified in Osthatheos Thirumeni. He was au-thentically Orthodox by being more than orthodox!

That is to say, Osthatheos Thirumeni had a radical understanding of Orthodoxy. Orthodox spirituality is an existential revolution. The best pointer to this, I believe, is the idea of offence, which is inalienable from Incarnation vis-à-vis the status quo (Mtt. 11:1-5). Incarnation is necessarily offensive to the status quo, because it activates possibilities, affirms ideals and values and advocates alternatives disruptive of its patterns and privileges. I doubt if the Orthodox Church realizes this clearly enough: Osthatheos Thirumeni’s most prophetic contribution to the Orthodox tradition was a radical view of Orthodoxy itself. He, like Parumala Thirumeni and Paulos Mar Gregorios, renewed and re-vivified the Orthodox tradi-tion by illuminating its larger horizons. In other words, he was a prophet to the tradition itself, besides being a prophetic voice in respect of the society at large.

Offence, as noted above, is intrinsic to the prophetic. That is why Jesus said that no prophet would be welcome among his own people. Jesus was Orthodox. He was in conflict. Wherever anti-life forces are in control, the Orthodox vision can-not but be in conflict with them. This is a necessary conflict; conflict that affirms life. Compromise is the alternative to conflict. Jesus, being quintessentially Ortho-dox -such orthodoxy is really the only authentic revolution in this world- was in conflict with the status quo; not because he chose to, but because it had to be so. Wherever this necessary offence is absent, the Orthodox tradition is either dor-mant or in compromise. It woke up in the soil of Kerala through Osthatheos Thi-rumeni. That ‘voice crying in the wilderness’ was heard as thunder and a lion’s roar, because the people had been tuned, in the general context, to the tame mu-sic of compromise.

In my own experience, the worst hindrance to the prophetic is the worldly idea of peace that makes cowards of most Christians. Peace is understood as absence of conflict. That is the world’s idea of peace. Hence Jesus emphasized, “My peace I give unto you, not as the world gives….” (Jn. 14:27). In almost every instance I am familiar with, when the moment of necessary conflict with entrenched forces of vested interests comes, our community becomes disquieted. People perceive it as irreligious! It is a mark of the robustness of the Malankara Orthodox tradition that the prophetic and the spiritually conflictual had a place within its incarnational engagement with society.

One more essential word about the Orthodox tradition before I take leave of my personal tribute to Osthatheos Thirumeni. I cannot refrain from mentioning this, as it points to the contemporary relevance and dynamism of the Orthodox tradi-tion.

Thirumeni was, by his own candid admission, an unpromising student. He failed twice in his school years. Yet, he became a globally respected spiritual thinker and a matchless communicator. That is exactly where the vibrancy of a tradition comes in. I shudder to think of Uzhakkadavil Georgekutty without the Orthodox Church. Where would he have ended up? In which organization, movement, or system in the world would such an unpromising boy, stuck neck-deep in poverty, have grown, like the biblical mustard seed (Mtt. 13:31), into a towering spiritual tree under which a multitude of people found welcome and encouragement?

In saying this, I am not unmindful of the role that Abraham Mar Thoma of the Mar Thoma Church played in Thirumeni’s life. But, even the catalytic role that this man of God played in the life of the budding spiritual genius could bear fruit because there was a tradition that sustained him. We see the same strength reflected in the lives of all the towering spiritual geniuses of the Orthodox Church. The Church nurtured them. They, in turn, enlivened the Orthodox Tradition and gave it a new vigour, reach and relevance. I hope very fervently that the Malankara Orthodox Church would prioritize this creatively spiritual aspect of its tradition for further development; especially at the present time when structures are, everywhere, becoming a greater priority than the people.

PART -II

As already mentioned, the reason I chose the present Gospel text for the com-memorative sermon is that this was the verse on which the young chemmachen (deacon) preached his first sermon. The morning, says the proverb, shows the day. Osthatheos Thirumeni was a clarion call, inviting everyone into the Kingdom of God. He knew there was an eligibility requirement for admission into this privi-lege: repentance.

What, then, is the Kingdom of God? How do we recognize its identity and pres-ence?

In the following reflections I shall venture, if only because of my uninformed im-pertinence, to meditate and mediate the message as Osthatheos Thirumeni would have thought out, in those distant and innocent days. He would have said something like the following-

The Kingdom of God, like all kingdoms, has a King. That’s nearly how the story of salvation begins, from the Eastern point of view. The Wise Men from the East came asking for the one who was born to be the King of the Jews (Mtt.2:2). They were both right and wrong. Right, to the extent that he was King. Wrong, to the extent that he was the King not merely of the Jews.

The prime purpose of Christian proclamation is the exaltation of this King of kings; the King who came to serve and to restore the lost -an agenda in which no earthly king has ever shown any interest. It is through this King that the Kingdom be-comes a tangible, feasible reality. He is, hence, the gate and the door to the King-dom (Jn. 10).

Secondly, this Kingdom has subjects, who are not exactly subjects. They are part-ners, instead. In history, all subjects have been exploited and millions sacrificed. War is nothing but human sacrifice at the diabolic altar of elite interests. The Kingdom-safeguard against this atrocity is partnership. History has not seen a sin-gle governance model in which the people at large -other than a few chosen from the socio-economic elite- have been even in notional partnership with the ruler. Partnership is dynamic equality. The world proffers static or theoretical equality only for propagandist purposes. Equality, in a general sense, has been a mirage in history; and that has been so, even in the so-called socialist countries. Human na-ture abhors equality; it revels in privilege, which stands on inequality. The privi-leged are gloried, first and foremost, by the under-privileged, who internalize ri-tuals and romances of inequality.

The harvest of partnership is fullness of life. In practical terms, it means the multi-faceted growth of personality. Those who have worked as faithful servants and partners with Jesus, have become wonders in the eyes of others. Growth is the cause for that wonder. Osthatheos Thirumeni was a radiant realization of that wonder. Preacher, theologian, missionary, author, administrator, social activist, and a great deal more…. All from that tiny seed called Georgekutty, in whom not many would have seen even a distant sign of promise!

Osthatheos Thirumeni, I am sure, would have emphasized, in connection with the biblical idea of partnership, the difference between work and service; for that dis-tinction, even though subtle, is crucial for understanding what it means to be in partnership with Jesus. It is being increasingly lost sight of that hospitality was the culture of work as ‘service’ in Jesus’ view. Adam was instructed not only to work in the garden but also to ‘take care of’ it. (Gen. 2:15). To take care of, is to accept and to cherish. It is to over-ride all barriers with the energy of love, which refuses to be channeled according to worldly patterns. Osthatheos Thirumeni was stri-kingly hospitable to all; not just to the members of the Orthodox Church, or to Christians alone. I saw this Orthodox trait most distinctly, and at close quarters in Paulos Mar Gregorios Thirumeni. He had, I dare say, more admirers in the non-Christian world than in the Christian fold. He accepted people of all kinds and sta-tions. His world had no lepers. From what I have read of Osthatheos Thirumeni, it is overwhelmingly clear that he was no different.

Work without the spirit of hospitality falls short of service. Partnership involves not mere work; it involves service. Jesus said, “For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” (Mk. 10:45). The word used is ‘serve’, not ‘work’. Service, as envisaged in the Bible, happens in partnership with Jesus. The hallmark of that partnership is hospitality. Hospitality is a precondition for transformation. Jesus calls us to, and into, himself so that we may become the new creation (2 Cor. 5:17). We have to be in Christ and he has to be in us (Jn. 15:4) for us to be in partnership. Partnership involves, therefore, a two-way hospitality. One-way hospitality bespeaks of either unila-teral charity or insolent inequality. Jesus accepts the worth of the Samaritan woman, by asking of her for a drink. It is only after thus accepting her that he re-veals himself as the living waters to which she too is entitled.

No work amounts to Christian service or missional partnership, Osthatheos Thi-rumeni would have emphasized, without this spirit of hospitality, or the large-heartedness of being open to all. That this was the essence of Jesus’ own outlook is abundantly clear: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” (Mtt. 11:28). It is the ultimate statement on unconditional hospi-tality. Accepting people into one’s own home, Mother Teresa used to say, if a far greater spiritual challenge than reaching out to them with charity where they are. Accepting others into oneself is infinitely more challenging.

The hallmark of service done in partnership with Jesus is that it is wholly free from profit motive. While commissioning and sending his disciples out Jesus said to them, “Freely you have received, freely give.” (Mtt. 10:8). The logic of this instruction becomes clear when we see it in light of hospitality. Think of inviting your friends to a meal at home and, as they depart after a satisfying meal, your thrusting a bill (realizing a comparatively nominal profit of 50% on cost) into their hands! It sounds sacrilegious vis-à-vis the idea of hospitality. Even more scandal-ous is, Thirumeni would say, to preach for profit! Or, do any Christian work for profit. That includes the ‘profit’ of popularity or fame or whatever. Hence it is that Jesus said that those who wish to be his disciples -that is to say, to be in partner-ship with him- must deny themselves, take up the cross and follow him (Mtt. 16:24).

The resource for this Kingdom partnership is faith, not funds. Here, I am pretty sure, Osthatheos Thirumeni would have dwelt upon the logic of this distinction and made it sparkle with clarity. If we are to understand the pitfalls that dot the path of spiritual work, we need to understand this “mammon-principle” for what it is. It is customary to interpret Mammon as money. Thirumeni would have disa-greed and added with a knowing smile -No, it is, in principle, your affinity to sol-ids. Consider the following example to see this principle more clearly.

In the 12th chapter of the Gospel According to St. Luke, we find Jesus teaching the people assembled to hear him, with much emphasis, regarding the ministry of the Holy Spirit. We see only one response recorded in the text to that most cardinal teaching. “Master, bid by brother to divide the property between us” (Lk. 12: 13). It took me a long, long while to understand the spiritual psychology of that man, and the universal relevance of the episode.

The point is that, given human nature, and given the choice, we would rather choose material assets to the resources of the Holy Spirit. The point involved here is not obscure. It is the choice between what is solid and what is non-material. Why do we prefer what is solid? Because it lends itself readily to our ownership and control. The problem with spiritual resources and forces is that they will not stay within our control. “The wind,” Jesus said to Nicodemus, “blows where it pleases. No one knows where it comes from, or where it goes.” That pulls the rug from under our feet! It makes a mockery of our penchant for control and owner-ship.

Faith is a resource that belongs to realities of this order; whereas finances belong to the domain of solids. It is because of our affinity to solids that we become ‘stone-hearted’. As we turn from the world to God, we would be given, according to Prophet Ezekiel, a heart of flesh in place of a heart of stone (36:26).

Or, consider this parableof the Kingdom: the parable of the royal banquet (Lk. 14:15-24). What is on offer is not just a banquet, but a way of life based on joy. This is, in other words, a spiritual banquet. What are the excuses offered by the invitees for not accepting this supreme privilege? Land, oxen, bride…. The pattern is the same. Left to ourselves, we cannot overcome the preference for solids. The ‘brides’ of this world do not realize that as long as human nature -including their own- remains fixed in this fashion, they are in peril of perpetual exploitation and discrimination. It is man’s affinity to solids that degrades a bride into a chattel. It is the same thing that makes Judas sell his master for silver -the quantity does not matter. It may be three million pieces now, in place of the thirty pieces then. Makes no difference. What matters is the affinity to, or preference for, solids. The most solid of all human strategy for self-preservation is, indubitably, the cross, the flint-hearted engine of torture.

Even overlooking constraints of time, Osthatheos Thirumeni would have empha-sized, with his characteristic flourish, that the Kingdom of God involves a re-location of the human condition from the wilderness-principle to the garden-principle. The Garden of Eden was, clearly, meant to be a prototype. Human per-sonality, individual life, home, church, society, nation, the world… all of them need to be established on the garden principle. What does this involve?

-The Garden is a symbol of the manifest and the un-manifest. Adam has to till the land, which is a metaphor for bringing to light hidden goodness and resources. What is manifest, is a small part of what is possible. Hence it is that Jesus urges us to ‘seek’ (Mtt. 7:7). We are to seek the fullness of everything. The alternative to this fullness is ‘part-ness’, which is the wilderness-principle. It breeds ‘thirst’; the thirst that kills. The woman of Samaria is a case in point. But for her timely, life-changing encounter with Jesus, she would have died of thirst!

-The Garden is a symbol of the harmony between bread and beauty. We are more than mere consumers. So, we cannot live by bread alone (Mtt. 4:4). We need beauty as well. But there is a problem with how we understand beauty. Beauty is a matter of wholeness. In ourselves we are never whole, or complete. For us to be whole, we have to be in partnership with God; for that was what we were created for. Beauty in the Bible is a spiritual thing. Even the feet of those who are in part-nership with God are beautiful. “How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news, who proclaim peace, who bring good tidings, who proclaim salvation, who say to Zion, ‘Your God reigns!’” (Isaiah 52:7).

-The idea of beauty, based on the garden-principle, is rooted, as seen earlier, in the partnership with God. This partnership has, hence, two major aspects -worship and service. Worship is symbolized by the sound of ‘foot steps’ in the garden (Gen.3:8). The foot steps are the rhythms in the spiritual garden of our personality. Worship in spirit and in truth is not an obligation, but the spiritual food for the wholeness of our being. But food is inseparable from service. To eat and not serve is to be a thief. That is the satanic principle. Jesus, the King of this Kingdom, is the role-model in all of this. He is the Servant par excellence. He is the Servant King! The Servant that makes kings of his flock.

-The garden principle is -and this is often overlooked- inseparable from the idea of depth. In the parable of the sower (Mtt.13:1ff), Jesus emphasizes the importance of depth for fruitfulness to happen. When Adam tills, he continually connects with depth. Farming is an on-going dialogue with the depth of the garden! In contrast, the wilderness principle implies a restless wandering -in the tradition of Cain- over the ‘face’ (or surface) of the earth. On the surface -estranged from depth- we can be only ‘wanderers’. The Kingdom of God is a state of stability, rootedness and fruitfulness, insofar as we abide in the King, and he in us.

Depth is the defining distinction between God and idols. Idols are all surface, no depth. So, they have eyes, but see not. Have ears that hear not. Have libs, but they neither move nor help. Gods of shallowness, they are incapable of compas-sion. Fruitfulness, whether of nature or of the Spirit, presupposes depth. The ‘fruit’ of the Spirit (Gal. 5: 22-23) implies depth. The culture of the Kingdom of God is one of depth, where no form of human authority runs. Only God reigns!

WHY REPENT?

Spirituality excludessuperfluities. Only that which is absolutely, irreducibly essen-tial is preserved as spiritual requirements. The cultures of the world thrive on ela-boration, proliferation and sophistication. The culture of the Kingdom operates on the contrary principle: that of simplification and reduction to bare essentials. Hence it is that Jesus says to Martha, who is staggering under the burden of man-made struggles based on shallow stereotypes. “Martha, Martha, you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed.” (Lk. 10:41).

There is only one eligibility requirement for entering the Kingdom of God. That requirement refers to a serious problem we have created for ourselves. Adam and Eve rejected partnership with God in favour of ‘equality with God’ to be attained through material means (Gen. 3:5). This initiated a shift in foundation for human nature from the spiritual to the material. And it is this that I pointed out earlier as the human affinity to solids; whereas the life principle is dynamic and fluid. It is the solid-affinity that orients human nature to the aberrations of ownership, which Jesus exposes through the parable of the tenants (Lk. 20: 9-17). The tenants become murderous when they shift from partnership to ownership. The core insight of this parable is that ownership mentality, in all its forms, is de facto theft. It implies an outlook of violence. We are either partners or thieves. No man can ever be owner of anything in this world. The earth is the Lord’s. Also, the fullness thereof.

Consider now the psychology of Cain. A murderer of brother, he experiences a neurotic need to found a city (Gen. 4:17). That casts a reflective light on why he killed his brother, Abel. Cain was a monopolist! He would brook no competition, much less sharing, vis-à-vis God’s blessings. What drives this mentality is the abso-lutization of material things. To Cain, it is not God, but blessings that matter. It is the outworking of the ‘equality-with-God-through-fruit’ principle.

By the time we come to the eleventh chapter of the book of Genesis, the fruit gives way to the Tower. The Tower, not God, will be the pivot of people’s unity. The consequence tells its own tale: the people get scattered over the face of the earth and are swept along by a tsunami of confusion. History deposits their great, great successors in Egypt, the land of slavery. That is a logical necessity. Slavery is an inevitable outcome of renouncing partnership with God. Human historical exis-tence is situated between the contrary poles of partnership and slavery. To reject one, is to fall into the other. Rousseau was right after all: man is born free; but everywhere he is in chains. How could it be otherwise, when it is the freedom of the far country that we prefer, as in the parable of the lost son (Lk. 15: 13)?

The Kingdom of God is a domain of freedom, but it is the freedom that issues from abiding in the Lord through obedience in love. Obeying Jesus is perfect free-dom. Abject obedience to the patterns of the world, disguised as freedom, cha-racterizes the kingdom of man. Dostoevsky’s insight, articulated through the Grand Inquisitor in Brothers Karamazov, is that bread and freedom cannot coex-ist. But it did, in the Garden of Eden! What the diabolic Spanish Cardinal, who admits his allegiance to Satan, withholds is the fact that this incompatibility be-tween bread and freedom is a curse humankind has invited upon itself by re-nouncing partnership with God.

Human liberation is the quintessential Kingdom agenda. Jesus came to set the captives free (Lk. 4:18). But human nature is so deeply conditioned in unfreedom that a shift from Egypt to the Promised Land turns out to be a protracted and near-death experience, symbolized by forty years of wandering in the wilderness. We have to die out of our habituated affinity to, our instinctive preference for, unfreedom. Even as we crave for freedom, we try to escape from freedom in a variety of ways. We are, says Dostoevsky, tormented by our freedom; for it burdens us with a fear of responsibility.

The call to repentance is the royal invitation to freedom! Or, in the words of the parable of the lost son, it is our home-coming to God.

“I will set out and go back to my father and say to him: Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son. Make me like one of your hired servants.” (Lk. 15:19).

But this home-coming is no excursion. It is a process of total transformation. It is tantamount to Lazar coming out of his tomb, from four days of putrefaction. (Jn. 11:38-44).

As the Psalmist says, God alone is our home (Ps. 46). It is not like any other home we have known hitherto. It’s a home of transformation, a dwelling place legiti-mate only for the new creation.

Osthatheos Thirumeni was the Baptist of our times. His was the voice crying in the wilderness. At all times, there are two contrary voices: the voice crying in the wil-derness and the voice of the wilderness. The wilderness too has its voice, its mu-sic, itsrhetoric. It tickles the ears attuned to the patterns of the world with the se-ductive music of slavery, the symphony of the flesh-pots of Egypt.

The defining aspect of the ‘voice crying in the wilderness’ is that it is in no confu-sion about itself. Osthatheos Thirumeni, like the Baptist, was always keen to af-firm that he was not the voice. Jesus alone was the voice of the Kingdom. The voice of the Baptist could shake the wilderness. Only the voice of Jesus can trans-form the wilderness into the Garden of Life. Hence it was that Thirumeni never failed to point all people to the Lord Jesus Christ as the author and the finisher, in the words of the writer of the Epistle to the Hebrews, of faith. He deemed himself as an instrument in the hands of his Master.

Today, as we commemorate this faithful servant of the King, we thank God for the sacrament of memories he has left behind: memories that can nourish and build up generations to be the redeemed flock of the Good Shepherd. So, even in commemorating Osthatheos Thirumeni, it is Jesus our Redeemer that we cele-brate.

Source:

OCP News Service

294554 299598Generally I do not read write-up on blogs, however I wish to say that this write-up extremely forced me to check out and do so! Your writing taste has been amazed me. Thanks, extremely excellent post. 162115

692695 135262I like this internet site because so much beneficial material on here : D. 608610

979112 848869Wonderful write-up. I appreciate your attention to this subject and I learned a great deal 216527