Toronto Based Researcher Works to Preserve Ancient Syriac Inscriptions

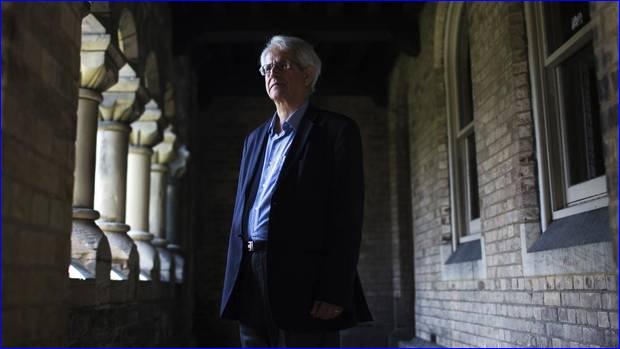

Amir Harrak, professor of Syriac and Aramaic languages at the University of Toronto, poses for a photo in Toronto on Aug. 8, 2014. Mr. Harrak has been working to preserve rare inscriptions written in the ancient language of Syriac and the university has the world’s largest photograph collection of Syriac inscriptions from Iraq (photo: Michelle Siu).

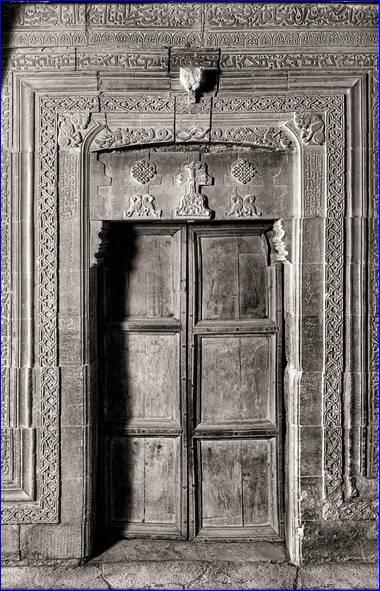

Mar Behnam (doorway) – Martyrion of Mar Behnam, c. 13th century. The Martyrion of M?r Behnam contains a trilingual inscription: Syriac, Arabic, and Uyghur (Old Turkic). Uyghur was used by the Mongols. This is the only known example of a Uyghur inscription in Iraq. It relates to a donation given to M?r Behnam by a Mongol Khan c. 1300 A.D. The monastery had been earlier ransacked by the Mongols; the donation was restitution. The b/w image was taken in the 1930’s; the original was from a glass plate negative.

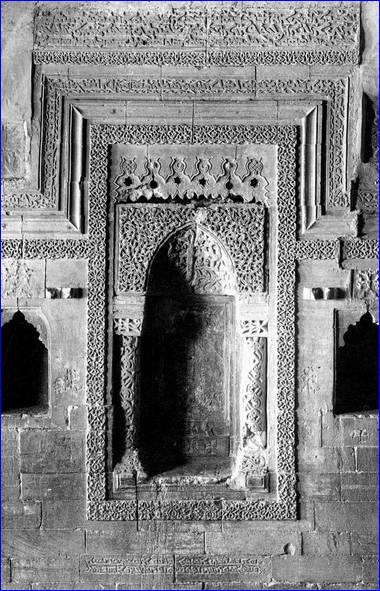

An image of the facade of the Mar Behnam Catholic monastery in Iraq is seen here. U of T’s Canadian Centre for Epigraphic Documents is home to the largest photo collection of Syriac inscriptions from Iraq.

More than a decade ago, Amir Harrak spent three sweltering summers in his native Iraq, photographing inscriptions written in the Classical Syriac language. The University of Toronto researcher had set out to document the centuries-old engravings, knowing many would eventually be lost.

In July, his worries returned when Islamic State militants took over the Catholic monastery of Mar Behnam in northern Iraq and detonated explosives that destroyed the Mosque of the Prophet Younis (Jonah), near the city of Mosul.

“It is catastrophic,” said Mr. Harrak, a professor of Syriac and Aramaic languages at U of T, home to the world’s largest photograph collection of Syriac inscriptions from Iraq, including several from Mar Behnam Monastery. “These inscriptions are not only local — some talk about world events, wars, epidemics. They contain all kinds of information, in addition, of course, to this Christian heritage of Iraq that dates basically from the time of the Apostles,” he said.

A dialect of a 3,000-year-old Semitic language, Syriac became the language of Christianity in the Middle East. Syriac inscriptions, dating back to the first century AD, are often written in poetic meter and have been found in Lebanon and Syria, throughout Iraq and Iran, and as far east as India and China — proof of an Eastern Christian tradition before European missionaries ventured to Asia to spread Western ideas of Christianity.

Unlike manuscripts, inscriptions are unedited documents, etched into materials such as stone, wood and metal, that reveal key cultural and historical details often left out in works of literature.

“If we have an inscription dating to, let’s say the second century, that — as the saying goes — is ‘in stone,'” said Colin Clarke, director of the Canadian Centre for Epigraphic Documents (CCED). “That record is frozen in time, whereas works of literature get rewritten as time goes on.”

Last November, the CCED — which is located at U of T but operates as an independent institution — opened access to a database of Syriac inscriptions, drawing from Mr. Harrak’s collection of more than 600 photographs, picturing many inscriptions from Iraq that are now damaged or lost. To document them, Mr. Harrak had spent long days cleaning and transcribing the inscriptions by hand.

Recently, scholars learned that the explosion at the Mosque of Jonah unearthed Syriac inscriptions from a church beneath the shrine. Mr. Harrak has been in contact with researchers in hopes that the inscriptions will be preserved and that photographs will be added to the CCED’s online catalogue.

The centre, founded in 2010, doesn’t receive funding and is staffed entirely by volunteers — librarians, archivists and graduate students who dedicate many hours to preserving and digitizing extant copies of inscriptions.

“The actual nuts and bolts of what we’re doing is done by information professionals. No other epigraphy project does that,” Mr. Clarke said. “I think that we’ve done remarkably well for a project that’s really only been in public for six to eight months.”

© Assyrian International News Agency.

977604 762790How a lot of an exciting piece of writing, continue creating companion 710529