Heresies and Councils

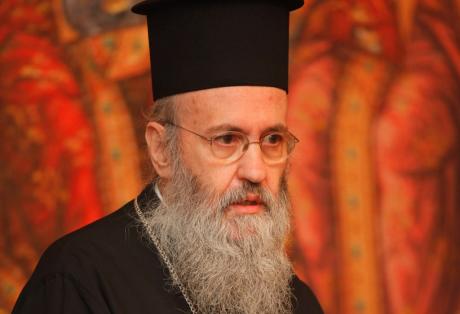

By Metropolitan Hierotheos of Nafpaktos, “Empirical Dogmatics”

14/2/14

In general, heresy is a deviation from the teaching of the Prophets, Apostles and Fathers; a deviation from the decisions of the Local and Ecumenical Councils, but also a change in the presuppositions of Orthodox dogma, which are holy hesychasm and the degrees of spiritual perfection, namely, purification, illumination and glorification, or praxis and theoria.

Councils of the Church

Councils were convened to deal with heresies, because the Church makes decisions through Councils. The model for this conciliar structure, as we havealready mentioned, was the first Apostolic Council. It is also clear from the Epistles of St Paul, in which he makes mention of his co-workers.

In Volume 1, in the chapter ‘The Divinely Inspired Theology of the Fathers’ it was particularly emphasised that the glorified Fathers validated the Ecumenical Councils, not the other way round. Here we shall examine the subject of Local and Ecumenical Councils and their necessity for the Church.

It needs to be understood that the Church functions and does its work in a specific place and time, and uses for its form and its canonical structure the external circumstances that it finds. In this manner, and for the sake of its unity, it adopted the same way of working as the society of that time.

“Something strange can be observed in history: the criteria by which the Church adapts to its surroundings can be traced back to Canon Law. The Church adjusts to the environment.

We see this very clearly from the development of the conciliar system in the early Church. The Church was adapting itself to the Roman environment. We see that the metropolitan is the bishop of a metropolis of a Roman province. All the other bishops in the Council are in small villages or towns. And the metropolitan is automatically the president of the Council. Translations from one see to another were never permitted in the early Church, so the bishops never contended for higher positions.”

This is how the metropolitan system and later the patriarchal system of ecclesiastical administration were created. Local Councils were convened on the basis of this administrative system, and later the Ecumenical Councils were convened, which defined the administrative system of the Church more thoroughly.

Local and Ecumenical Councils

Councils are divided into Local Councils, which are made up of bishops of particular provinces, and Ecumenical Councils, in which all the bishops of theRoman Empire take part. First of all, the decisions of the Councils have great significance, like the texts of Holy Scripture. In the Orthodox Church we speak of Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition, and Holy Tradition also includes the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils. These texts are medicines so that one can be led to purification, illumination and glorification. It is only when someone reaches glorification, in the experience of ineffable words, that all created words and concepts are transcended, without being abolished.

Local Councils, which were convened in the various provinces, were more ancient and more ecclesiastical conciliar institutions.

“If no Ecumenical Council had taken place, if the Church had not prevailed in the Roman Empire, and if the Emperors had not decided that the Orthodox Church would be the official Church of the state, what institution would there be? Would the institution be what it always had been? The bishops were organised into Local Councils, which were the Councils that supervised the ordination of bishops. They supervised the ordination, and then the Councils would send each other letters of commendation. In particular, when the leader of a Council was chosen, they would send letters to other Councils announcing the election and the ordination. And they would send representatives to take part in the ordination. So when a heresy appeared in a Church, it was condemned by the Church itself, and then the decisions were sent to other Churches and everyone agreed that the one who had been condemned was a heretic.”

Arius was condemned as a heretic by the Local Council in Alexandria, where he was serving as a priest, when he asserted that the Word was created.

Before the First Ecumenical Council was convened, many heresies had appeared in the Church and all had been dealt with by Local Councils. The First Ecumenical Council was convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine to ascertain what the faith of the Church was. Other Emperors wanted to establish Christianity as the official religion of the state. Exactly the same happened with later Ecumenical Councils.

“There are some foolish people who believe that Arianism was condemned at the First Ecumenical Council. This is nonsense. It was first condemned in Alexandria, and the condemnation of Arianism in Alexandria was accepted by all the Local Councils of the Orthodox Church, in the West and the East. The condemnation starts from Alexandria and afterwards the condemnation is communicated to all the other Churches. The condemnation of Arius is accepted by all the Orthodox.

In other words, there was uniformity in faith before the First Ecumenical Council was convened. Afterwards the First Ecumenical Council was called and the bishops, who had already condemned him in Local Councils, condemned Arius. Arianism was not condemned for the first time at the First Ecumenical Council.

Now, if there had not been a Christian Emperor, and if certain leaders of the Roman state had not wished to establish Christianity as the religion of the Roman state, we would not have had the First Ecumenical Council, nor the Second, Third, Eighth and so on. We would have had Local Councils of bishops, which dealt with heresy and communicated their decision to all the other Councils of the Church. These other Councils immediately recognised that this man was a heretic and had been rightly condemned.

Before the First Ecumenical Council the first heresy in the Church was not that of Arius. There were other heresies as well. The most striking heresies were those of the Sabellians and the Samosatenes. We have two heresies, that of Paul of Samosata and that of Sabellius, which seem to be opposite extremes, but are not opposite extremes.”

The Ecumenical Councils are actually ‘an extension and amalgamation’ of all the Local Councils. They were the result of the need of the state to introduce the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils into its legislation, so that unity would prevail in the Roman Empire.

“Why did the First Ecumenical Council take place? Because we have the Arian dispute. Arianism had broken out as a heresy within the bosom of the Church, and the state had recognised the Church as the religion of the Empire. We have a Church recognised by the state. And now the bishops are quarreling among themselves.

One party is Arian and the other is Orthodox. Given that it is the official religion of the state, the state ought to know what the faith of the Church is. So the Emperor is obliged to convene representatives of all the Orthodox Councils of the Church to assemble somewhere and deal with all the issues. They must deal with the issue of Pascha – because the Empire wants all Christians, at least within the Empire, to celebrate Pascha together. Christians in Asia Minor celebrated on the equinox, the fourteenth; they celebrated Pascha when the Jews celebrated Passover, on any day of the week. All the others celebrated Easter on the Sunday after the Jewish Passover. This was the practice of the Church.

So this was another issue that concerned the Council, perhaps even more than the dogma of Arius. Arius was immediately condemned, because they all knew that he was a heretic. There was not much discussion at the Council about Arius’s teaching. So Arius had already been condemned by all the Local Councils, apart from the Councils where there was no Orthodox Archbishop, for there were certain Churches that had an Arian tendency.

In general it is easy to conclude from studying the acts of the Ecumenical Councils, at least those that survive, that the Council is an extension and amalgamation of all the Local Councils, and that the Council was not convened for the needs of the Church, for the Church had no need of any Ecumenical Council. All the heresies that were condemned in Ecumenical Councils had already been condemned in Local Councils. The Church, therefore, had no need for this Council. The state needed the Council so that it could decree Orthodoxy and the Canon Law of the Orthodox Churches as laws of the state.”

The Church knew that Arius was a heretic. The First Ecumenical Council confirmed and ratified that Arius was a heretic. Some people, however, treat the Councils as though the Fathers argued with Arius rationally in a quest for the truth.

“How did the First Ecumenical Council spend its time? Our own people reply speculatively. There was a philosophy of the Fathers about God, and the Christian philosophers argued among themselves about God – Arius with Athanasios, and with this one and the other. Then the Holy Spirit came to say what was Orthodox and what was heretical.

So they did not know what was heretical until the Council came and condemned the heresy. They found out at the Council what was heretical. Didn’t they know that Arius was a heretic before the Council? Was it necessary for the Council to be convened to tell us that Arius was a heretic? This is like saying today that a charlatan, a butcher-surgeon, appears and two other doctors do not know that he is a butcher until they gather at a meeting and decide that he is a butcher. And they don’t know that he is a butcher because he kills people. It is not enough that he kills patients and they have to make a decision that he is a butcher.

Something similar happens. Perhaps we not know that Arius is a heretic, as he is a good man and teaches fine, philosophical things, and the Council has to be convened to show us that Arius is a heretic?”

Whenever a heresy appeared, the Council countered it using theological and ecclesiastical criteria. However, when the state wanted to enact ecclesiastical laws for the unity of the Empire, it wanted to be informed officially by the bishops of all the provinces of their decision. The Ecumenical Councils operated in this context.

“We have the Second Ecumenical Council. Well, did the Churches wait for the Second Ecumenical Council to be convened for the Pneumatomachians and Eunomians to be condemned? The bishops themselves had already well and truly sorted out the Pneumatomachians and Eunomians before the Second Ecumenical Council was convened, and their teachings had already been condemned by Local Councils. Then the Second Ecumenical Council assembles and condemns them. It repeats the condemnation.

The same happens with the Third Ecumenical Council. There Nestorius had already been officially condemned by the Council of Alexandria. The decision had been communicated to other Churches. The two Churches which did not accept the decision made in Alexandria were the Church of Constantinople, because Nestorius himself was the Patriarch, and then the Church of Antioch, which was divided, because all the followers of Theodore of Mopsuestia were in Antioch. So there was a difficulty; radical disagreement existed on the issue of Nestorius. The Church of Rome immediately condemned Nestorius.”

“Then we have the Fourth Ecumenical Council. Once again, Eutyches was not condemned by the Fourth Ecumenical Council. He had been condemned in the Local Councils of Constantinople. These decisions were accepted by Rome and Antioch, whereas Alexandria was in two minds, as it was uncertain what the teaching of Eutyches was. What is certain, however, is that they condemned the heresy of Eutyches, without referring to Eutyches himself, because they were not sure whether Eutyches was teaching the things of which he was accused.”

Ecumenical Councils were instituted by the Roman Empire in order to solve ecclesiastical problems that involved all the provinces, so that their decisions would become laws of the state and there would be peace in the Empire. This means that the Ecumenical Councils did not supersede or replace the Local Councils, but they validated them on a universal basis. As the state was aiming for political unity, it was also interested in its religious unity.

“The Ecumenical Councils are an assembly of Local Councils on an Imperial scale. In other words, the Emperor calls the Ecumenical Council, so that the Local Councils could inform the state, the Empire, about the faith and practice of the Church. Then it was an opportunity for the Church as a whole, or the local Churches, to come together and inform the state about the faith of the Church, as well as about the practice of the Church, so that the decisions they took would be the same throughout the Empire.

For that reason, the Canons of the Ecumenical Councils were not meant to supplant the Canons of the Local Councils. The Local Councils had Canons; there were Canons enacted by Local Councils, Canons about the functioning of the Council or of the various Churches within the Council. It was an opportunity to formalise the common practice of the Church and to draw up Canons of Ecumenical Councils, which would be recognised by the state as the laws of the Church. And the formulation of the faith and everything concerning the faith.”

“When one studies carefully the historical foundations, the historical context and the tradition of the Church that existed up until the First Ecumenical Council, it becomes clear that this major conflict between the Arians and the Orthodox broke out and the state wanted to take a view on this issue. The idea was that, while the state was always divided on the subject of religion, and unity was based mainly on weapons and the police – there was also national identity among the Romans, particularly after Caracalla’s legislation of 212, when all free citizens within the Empire acquired Roman nationality and the rights of a Roman citizen, from 212 until 313. A hundred and one years later the idea was that, in order for this Empire to survive, grow, expand and increase in strength, religious unity was also required in the state.”

Although the Ecumenical Councils were created by the Roman state, they still have theological significance, because bishops took part in them who discussed theological and dogmatic issues, and they extended the work of Local Councils. Local Councils are also divinely inspired, if they are convened according to Orthodox preconditions.

“The institution of Ecumenical Councils is purely and solely Roman. If the Church had not been recognised by the Roman Empire, I doubt whether we would have had Ecumenical Councils, because they were essentially the work of the Emperors.

Since the fall of Constantinople, therefore, some of our own people hold the view that we cannot have Ecumenical Councils now, as we do not have an Emperor. You know, professors of Canon Law are now attempting to replace the Emperor with the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Be that as it may, we have, on the one hand, the historical issue and, on the other, the theological and dogmatic issue. Even before the fall of Constantinople the same idea occurred to us, that the supreme authority in the Church is the Ecumenical Council, and that only the Ecumenical Council can authoritatively enact things that the Hierarchy will perform during the historical development of the Church. This is connected, at least today, with the subject of divine inspiration.

Everyone usually agrees that Holy Scripture is divinely inspired. The writers of Holy Scripture have divine inspiration. Then there are those who believe that there is also divine inspiration at the Ecumenical Council. Few of those who hold this view accept that a Local Council can be divinely inspired. It is the Ecumenical Council that has divine inspiration, which is also expressed through the Hierarchy, when the Hierarchy agrees on an issue.”

At the Ecumenical Councils the Fathers did not take part only as individuals, but as representatives of entire local Churches. No distinction was made between Local and Ecumenical Councils on the grounds that the former were inferior and the latter superior; the clue to the difference was that Ecumenical Councils were an extension of Local Councils.

“So we have the Roman Senate, the assembly of Roman elders and the Senate of the Romans, and we have the Emperor, who enacted the laws. The Senate accepted the decrees of the Emperor and placed the seal upon them. When the Emperor signed a law, it became the law of the state and was included in Roman law from then onwards. The state used the same legislative method in religious matters. The Emperor was not able to decide what the dogma of the Church was. The Church had to decide. Constantine the Great, as a result of an inspiration, I don’t know if it was divine inspiration or not, convened the First Ecumenical Council, not only to find out what the faith of the Church was, but in order to lay down the faith of the Church.

So the Church gathered at the Ecumenical Council. All the Churches sent representatives, and it is extremely significant that the Local Councils are represented at the Ecumenical Council. The bishops do not attend as bishops. The bishops always go to Ecumenical Councils as members of the Church to which theybelong. The leader of every delegation is the metropolitan or the archbishop of every Church, and then there is the patriarch or the patriarch’s representative.

At all the Ecumenical Councils, the bishops do not speak as individuals, as members of the Pan-Orthodox Church. They speak as representatives of their Local Council. As happens today at the Pan-Orthodox Conference. No one goes to the Pan-Orthodox Conference to represent himself. They all go as representatives of their Church, and every Church has the same representation, the same vote, and so on. So in the Acts of the Councils that are preserved, the bishops do not speak at the Councils; the metropolitans speak. The leader of each Council speaks, or someone whom he assigns to state the opinion of the Council. In this way, the view of the local Church is expressed at every Ecumenical Council

The classic example can be seen at the Fourth Ecumenical Council. When the bishops of Egypt were called upon to sign the Acts, they said, ‘We cannot sign the Acts, because we do not have an archbishop.’ In other words, in order to sign the Acts, the Church of Egypt had to meet as a Church, with its president aschairman, and the Council of Egypt had to decide to sign the Acts. However they did not have a president, because Dioscorus had been condemned by the Fourth Ecumenical Council.

This excuse is a clear indication of how the Local Councils saw the Ecumenical Council. They did not regard the Ecumenical Council as superior to the Local Council, though also not as inferior. It is neither higher nor lower, but is simply an extension of the Local Council. Another very significant point is that the Second Ecumenical Council did not add to the Creed, but corrected the Creed on the basis of new terminology, which did not exist at the time of the First Ecumenical Council. There is a correction from the point of view of terminology, but not with regard to teaching; nothing was added from the point of view of teaching. Some adjustments were made to the terminology, which had now prevailed in all the Churches. Because the Churches had a common faith, but they wanted to have a common terminology as well. It was no longer sufficient to have a common faith; they also had to have a common terminology.

They lay down Canons in order that all the Churches will share the same practice. It was a good opportunity to co-ordinate Canon Law as well. They took the opportunity to do so. But why did they do this? Because the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils and the Canons of the Ecumenical Councils, as long as they are signed by the Emperor, become the law of the state. So this practice of the Local Church had to enter Canon Law, which now for the first time is made on the basis of the united Empire, so that it can be recorded in Roman law. Thus every judge, every Roman official, is obliged to implement this decision, which now becomes the law of the state. So we have the First Ecumenical Council, the Second – a whole series of Ecumenical Councils with canonical and dogmatic decisions that become laws of the land.

Ecumenical Councils should be seen in this context. The modern ‘Orthodox’ view, that the Council is convened in order for the Church to find out what it is teaching, or to decide what it should teach, is nonsense. Absolute nonsense. It bears no relation at all to the reality.”

The Emperors who convoked Ecumenical Councils not only wanted to know the views of local Churches, so that there would be common legislation, but had also discerned the therapeutic character of the Orthodox Church. They wanted to impose the Orthodox faith as a therapeutic system for the inhabitants of the Empire. In other words, they wanted the cohesion of their citizens to be based on a true therapeutic method.

“The basic criterion of the Emperor and the state was that they knew that the Church cured the noetic faculty through purification and illumination. Everyone knew that; there was no one who didn’t know that. In the Acts of the Councils one sees the Emperor saying: ‘Let everyone judge with his nous.’ ‘Everyone…with his nous’ does not mean ‘with his reason’. It means with the spirit that he has in his heart.”

The prevailing view today is that an Ecumenical Council cannot be convened as there is no Emperor to convene it. For that reason there is talk of a Pan-Orthodox Council, or a Holy and Great Council. Pan-Orthodox Councils are convened by the Ecumenical Patriarch, whereas the familiar Ecumenical Councils were called by the Roman Emperor.

“The [an Orthodox] Patriarch of Constantinople has the right to call an Ecumenical Council, with the consent of all the other Churches. Well, there is no doubt that such a right exists. If the Orthodox Churches want to consult one another and to gather at a Council, that is their right.

This must not be confused, however, with the tradition of the Ecumenical Councils. The tradition of the Ecumenical Councils means the tradition of the Imperial Councils. When the Romans referred to the oikoumene (the inhabited world) they meant what is called in Latin the universa Romano,, the Roman Universe, the Ecumenical (Universal) Empire. They did not mean the whole world: they meant the Empire.

For that reason in Constantinople there was an ecumenical teacher, an ecumenical this, that and the other. There was an ‘ecumenical’ version of everything. The top man in the Empire in any post had the title ‘ecumenical’, not just the Ecumenical Patriarch. The word ‘ecumenical’ in Constantinople was used in the sense of ‘imperial’, as we would refer today to a governmental official.”

Orthodox Preconditions for Councils

The historical background to Ecumenical Councils that we looked at above does not alter their great value and significance, as they acquired great importance in the life of the Church. Why they were convened and who convoked them does not matter. Their value lies in the theological and theological preconditions on which they were convened.

“The basic precondition, not only for Ecumenical Councils but for Local Councils as well, is that those who attend a Local or Ecumenical Council should be at least in the state of illumination. But the state of illumination does not begin when they say the prayer at the start of an Ecumenical Council. That is not when illumination begins.

Certain fundamentalist Orthodox – I don’t know how to describe it – imagine that the historical bishops were like bishops today, who have no idea about dogmas, but have dogmatic experts at their side, advisers who advise them about dogmas. The bishop is a good man who is involved with orphanages, homes for elderly people, hospitals, good works, building churches, and goodness knows what else. He collects funds to help the poor earthquake victims. That is the bishop: a man of action, or perhaps a man on the boil. Because a mutual friend, a metropolitan, says that his spiritual father used to say: ‘Toil, toil, toil then boil, boil and steam away’. In other words, at the end nothing is left.

Some people imagine that all these bishops gathered, who as theology students gained only five marks in their examinations and understood nothing. And when they met, the Holy Spirit came like an axe and struck them a blow on the head. The head opened up, in went the Holy Spirit, and then words of wisdom came out of their mouths. He intervened at the Ecumenical Council or at a Local Council and illuminated the bishops in this manner, so that they reached correct decisions.”

What determines that a Local or Ecumenical Council is Orthodox is whether the majority of the bishops who take part in it are in the state of illumination of the nous. Studying the Orthodox Local and Ecumenical Councils reveals that their decisions are Orthodox because they were based on Fathers who not only had theoretical knowledge of the theology of the Church, but were bearers of the revelation. Thus the glorified Fathers gave validity to the Council, not the Council to the Fathers.